Un adulto masculino señala el contorno de un hígado y pinta una vesícula biliar en su abdomen.

Un adulto masculino señala el contorno de un hígado y pinta una vesícula biliar en su abdomen. Los síntomas de un ataque de vesícula biliar incluyen:

Ilustración del sistema digestivo con cálculos biliares y primer plano de cálculos biliares en la vesícula biliar, un cálculo que también pasó a la conducto cístico.

Ilustración del sistema digestivo con cálculos biliares y primer plano de cálculos biliares en la vesícula biliar, un cálculo que también pasó a la conducto cístico. Los cálculos biliares (a menudo mal escritos como cálculos biliares) son piedras que se forman en la bilis (bilis) dentro de la vesícula biliar. (La vesícula biliar es un órgano en forma de pera justo debajo del hígado que almacena la bilis secretada por el hígado). Los cálculos biliares alcanzan un tamaño de entre un dieciseisavo de pulgada y varias pulgadas.

Desde el conducto biliar, la bilis puede fluir desde dos direcciones diferentes.

Una vez en la vesícula biliar, la bilis se concentra mediante la eliminación (absorción) de agua. Durante una comida, el músculo que forma la pared de la vesícula biliar se contrae y exprime la bilis concentrada en la vesícula biliar a través del conducto cístico hacia el conducto biliar común y luego hacia el intestino. (La bilis concentrada es mucho más eficaz para la digestión que la bilis no concentrada que va del hígado directamente al intestino). El momento de la contracción de la vesícula biliar, durante una comida, permite que la bilis concentrada de la vesícula biliar se mezcle con los alimentos.

Los cálculos biliares generalmente se forman en la vesícula biliar; sin embargo, también pueden formarse en cualquier lugar donde haya bilis:en los conductos intrahepáticos, hepáticos, biliares comunes y císticos.

Los cálculos biliares también pueden moverse en la bilis, por ejemplo, desde la vesícula biliar hacia el cístico o el conducto común.

Un hombre experimenta dolor por un cólico biliar. El síntoma más común de los cálculos biliares es el cólico biliar.

Un hombre experimenta dolor por un cólico biliar. El síntoma más común de los cálculos biliares es el cólico biliar. La mayoría de las personas con cálculos biliares no tienen signos ni síntomas y no saben que tienen cálculos biliares. (Los cálculos biliares son "silenciosos".) Estos cálculos biliares a menudo se encuentran como resultado de pruebas (por ejemplo, ultrasonido o radiografías del abdomen) realizadas mientras se evalúan condiciones médicas distintas de los cálculos biliares. Sin embargo, los síntomas pueden aparecer más tarde en la vida, después de muchos años sin síntomas. Por lo tanto, durante un período de cinco años, aproximadamente el 10 % de las personas con cálculos biliares silenciosos desarrollarán síntomas. Una vez que se desarrollan los síntomas, es probable que continúen y, a menudo, empeoren.

Cuando se presentan signos y síntomas de cálculos biliares, casi siempre ocurren porque los cálculos biliares obstruyen los conductos biliares.

El síntoma más común de los cálculos biliares es el cólico biliar. El cólico biliar es un tipo de dolor muy específico, que ocurre como síntoma principal o único en el 80% de las personas con cálculos biliares que desarrollan síntomas. El cólico biliar ocurre cuando los conductos biliares (conductos císticos, hepáticos o conductos biliares comunes) se bloquean repentinamente por un cálculo biliar. La obstrucción que progresa lentamente, como por un tumor, no causa cólico biliar. Detrás de la obstrucción, se acumula líquido y distiende los conductos y la vesícula biliar. En el caso de obstrucción del conducto hepático o del colédoco, esto se debe a la secreción continua de bilis por parte del hígado. En el caso de obstrucción del conducto cístico, la pared de la vesícula biliar secreta líquido hacia la vesícula biliar. La distensión de los conductos o de la vesícula biliar provoca cólico biliar.

De manera característica, el cólico biliar aparece repentinamente o aumenta rápidamente hasta alcanzar su punto máximo en unos pocos minutos.

El cólico biliar es un síntoma recurrente. Una vez que ocurre el primer episodio, es probable que haya otros episodios. Además, existe un patrón de recurrencia para cada individuo, es decir, en algunos individuos los episodios tienden a ser frecuentes mientras que en otros son infrecuentes. La mayoría de las personas que desarrollan cólico biliar no desarrollan colecistitis u otras complicaciones. Existe la idea errónea de que la contracción de la vesícula biliar es lo que causa la obstrucción de los conductos y el cólico biliar. Comer, incluso alimentos grasos, no causa cólico biliar; la mayoría de los episodios de cólico biliar ocurren durante la noche, mucho después de que la vesícula biliar se haya vaciado.

Se culpa a los cálculos biliares por muchos síntomas que no causan. Entre los síntomas que no causan los cálculos biliares son:

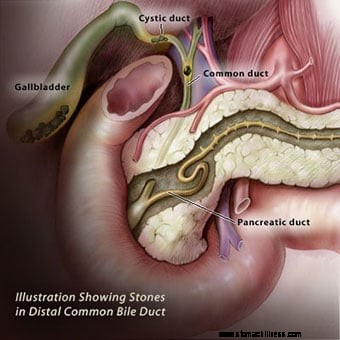

Ilustración que muestra cálculos biliares en la vesícula biliar, así como en el conducto biliar común distal. El conducto biliar común tiene una pared muscular.

Ilustración que muestra cálculos biliares en la vesícula biliar, así como en el conducto biliar común distal. El conducto biliar común tiene una pared muscular. La extirpación de la vesícula biliar (colecistectomía) debería eliminar todos los síntomas relacionados con los cálculos biliares excepto en tres situaciones:

La posibilidad de cálculos biliares en los conductos puede investigarse con CPRM, ecografía endoscópica y CPRE. En raras ocasiones, los síntomas parecidos a los cálculos biliares pueden ser causados por una afección llamada disfunción del esfínter de Oddi, que se analiza a continuación.

El conducto biliar común tiene una pared muscular. Los últimos centímetros del músculo del conducto biliar común inmediatamente antes de que el conducto se una al duodeno comprenden el esfínter de Oddi. El esfínter de Oddi controla el flujo de bilis. Dado que el conducto pancreático generalmente se une al conducto biliar común poco antes de que ingrese al duodeno, el esfínter también controla el flujo de líquido desde el conducto pancreático. Cuando el músculo del esfínter se tensa, cierra el flujo de bilis y líquido pancreático. Cuando se relaja, la bilis y el líquido pancreático vuelven a fluir hacia el duodeno, por ejemplo, después de una comida. El esfínter puede cicatrizarse y el conducto se estrecha por la cicatrización. (Se desconoce la causa de la cicatrización). El esfínter también puede tener espasmos intermitentes. En cualquier caso, el flujo de bilis y líquido pancreático puede detenerse abruptamente de manera intermitente, simulando los efectos de un cálculo biliar que causa cólico biliar y pancreatitis.

El diagnóstico de disfunción del esfínter de Oddi puede ser difícil de realizar. La mejor prueba de diagnóstico requiere un procedimiento endoscópico con el mismo tipo de endoscopio que la CPRE. Sin embargo, en lugar de llenar los conductos con tinte, se mide la presión dentro del esfínter. Si la presión es anormalmente alta, es probable que se produzcan cicatrices o espasmos en el esfínter. El tratamiento para la disfunción del esfínter de Oddi es la esfinterotomía (descrita anteriormente). La medición de las enzimas hepáticas y pancreáticas en la sangre también puede ser útil para diagnosticar la disfunción del esfínter.

Colección de cálculos biliares de varios tamaños y formas.

Colección de cálculos biliares de varios tamaños y formas. Los cálculos biliares pueden ser de uno a cientos, y varían en tamaño desde un milímetro hasta cuatro o cinco centímetros. Cuando hay uno o solo unos pocos cálculos biliares, tienden a ser redondos. Cuando hay un gran número de cálculos biliares, tienden a tener facetas debido al roce de un cálculo biliar con otro. Los cálculos biliares de pigmento marrón pueden ser desmenuzables e irregulares.

Los cálculos biliares pueden salir de la vesícula biliar o de los conductos, especialmente si son pequeños. Es el paso de los cálculos biliares lo que conduce a muchas de sus complicaciones.

Los cálculos biliares son comunes; ocurren en aproximadamente el 20% de las mujeres en los EE. UU., Canadá y Europa, pero existe una gran variación en la prevalencia entre los diferentes grupos étnicos. Por ejemplo, los cálculos biliares ocurren de 1 ½ a 2 veces más comúnmente en los escandinavos y los mexicoamericanos. Entre los indios americanos, la prevalencia de cálculos biliares es superior al 80%. Estas diferencias probablemente se deban a factores genéticos (hereditarios). Los parientes de primer grado (padres, hermanos e hijos) de personas con cálculos biliares tienen 1 ½ veces más probabilidades de tener cálculos biliares que si no tienen un pariente de primer grado con cálculos biliares. Más apoyo para una predisposición genética proviene de estudios de gemelos. Por lo tanto, entre pares de gemelos no idénticos (que comparten el 50% de sus genes entre sí), ambos individuos de un par tienen cálculos biliares el 8% del tiempo. Entre pares idénticos de gemelos (que comparten el 100 % de sus genes entre sí), ambos individuos tienen cálculos biliares el 23 % del tiempo.

Varias condiciones están asociadas con la formación de cálculos biliares, y la forma en que causan cálculos biliares puede variar. (Consulte los riesgos de los cálculos biliares).

Los cálculos biliares de colesterol se componen principalmente de colesterol. Hay otros dos procesos que promueven la formación de cálculos biliares de colesterol.

Los cálculos biliares de colesterol se componen principalmente de colesterol. Hay otros dos procesos que promueven la formación de cálculos biliares de colesterol. Hay varios tipos de cálculos biliares y cada tipo tiene una causa diferente.

Los cálculos biliares de colesterol se componen principalmente de colesterol. Son el tipo más común de cálculos biliares y comprenden el 80 % de los cálculos biliares en personas de Europa y América. El colesterol es una de las sustancias (sustancias químicas) que las células del hígado secretan en la bilis. La secreción de colesterol en la bilis es un mecanismo importante por el cual el hígado elimina el exceso de colesterol del cuerpo.

Para que la bilis transporte colesterol, el colesterol debe disolverse en la bilis. Sin embargo, el colesterol es grasa y la bilis es una solución acuosa o acuosa; las grasas no se disuelven en soluciones acuosas. Para hacer que el colesterol se disuelva en la bilis, el hígado también segrega dos detergentes, ácidos biliares y lecitina, en la bilis. Estos detergentes, al igual que los lavavajillas, disuelven el colesterol graso para que pueda ser transportado por la bilis a través de los conductos. Si el hígado segrega demasiado colesterol para la cantidad de ácidos biliares y lecitina que segrega, parte del colesterol no se disuelve. De manera similar, si el hígado no secreta suficientes ácidos biliares y lecitina, parte del colesterol no se disuelve. En cualquier caso, el colesterol no disuelto se pega y forma partículas de colesterol que aumentan de tamaño y finalmente se convierten en cálculos biliares.

Otros dos procesos promueven la formación de cálculos biliares de colesterol, aunque ninguno de los procesos puede causar la formación de cálculos biliares de colesterol.

Los cálculos biliares de pigmento son el segundo tipo más común de cálculos biliares.

Los cálculos biliares de pigmento son el segundo tipo más común de cálculos biliares. Los cálculos biliares de pigmento son el segundo tipo más común de cálculos biliares. Aunque los cálculos biliares de pigmento comprenden solo el 15% de los cálculos biliares en personas de Europa y las Américas, son más comunes que los cálculos biliares de colesterol en el sudeste asiático. Hay dos tipos de cálculos biliares de pigmento:1) cálculos biliares de pigmento negro y 2) cálculos biliares de pigmento marrón.

El pigmento es un producto de desecho formado a partir de la hemoglobina, la sustancia química que transporta oxígeno en los glóbulos rojos. La hemoglobina de los glóbulos rojos viejos que se destruye se convierte en una sustancia química llamada bilirrubina y se libera en la sangre. El hígado elimina la bilirrubina de la sangre. El hígado modifica la bilirrubina y secreta la bilirrubina modificada en la bilis para que pueda ser eliminada del cuerpo.

Cálculos biliares de pigmento negro: Si hay demasiada bilirrubina en la bilis, la bilirrubina se combina con otros constituyentes de la bilis, por ejemplo, calcio, para formar pigmento (llamado así porque es de color marrón oscuro). El pigmento se disuelve mal en la bilis y, como el colesterol, se pega y forma partículas que aumentan de tamaño y eventualmente se convierten en cálculos biliares. Los cálculos biliares de pigmento que se forman de esta manera se denominan cálculos biliares de pigmento negro porque son negros y duros.

Cálculos biliares de pigmento marrón: Si hay una contracción reducida de la vesícula biliar u obstrucción del flujo de bilis a través de los conductos, las bacterias pueden ascender desde el duodeno hacia los conductos biliares y la vesícula biliar. Las bacterias alteran la bilirrubina en los conductos y la vesícula biliar, y la bilirrubina alterada luego se combina con el calcio para formar pigmento. Luego, el pigmento se combina con las grasas de la bilis (colesterol y ácidos grasos de la lecitina) para formar partículas que se convierten en cálculos biliares. Este tipo de cálculo biliar se llama cálculo biliar de pigmento marrón porque es más marrón que negro. También es más suave que los cálculos biliares de pigmento negro.

Otros tipos de cálculos biliares. Otros tipos de cálculos biliares son raros. Quizás el tipo más interesante es el cálculo biliar que se forma en pacientes que toman el antibiótico ceftriaxona (Rocephin). La ceftriaxona es inusual porque se elimina del cuerpo en la bilis en altas concentraciones. Se combina con el calcio en la bilis y se vuelve insoluble. Al igual que el colesterol y el pigmento, la ceftriaxona y el calcio insolubles forman partículas que se convierten en cálculos biliares. Afortunadamente, la mayoría de estos cálculos biliares desaparecen una vez que se suspende el antibiótico; sin embargo, aún pueden causar problemas hasta que desaparezcan. Otro tipo raro de cálculo biliar se forma a partir del carbonato de calcio.

The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include gender, age, obesity, pregnancy, birth control pills and hormone therapy, rapid weight loss, Crohn's disease, and increased blood triglycerides.

The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include gender, age, obesity, pregnancy, birth control pills and hormone therapy, rapid weight loss, Crohn's disease, and increased blood triglycerides. There is no relationship between cholesterol in the blood and cholesterol gallstones. Individuals with elevated blood cholesterol do not have an increased prevalence of cholesterol gallstones. A common misconception is that diet is responsible for the development of cholesterol gallstones, however, it isn't. The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include:

A female doctor sits next to an ultrasound machine.

A female doctor sits next to an ultrasound machine. Gallstones are diagnosed in one of two situations.

Ultrasonography is the most important means of diagnosing gallstones. Standard computerized tomography (CT or CAT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may occasionally demonstrate gallstones; however, they are not as useful compared to ultrasonography because they miss gallstones.

Ultrasonography is a radiological technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the organs and structures of the body. The sound waves are emitted from a device called a transducer and are sent through the body's tissues. The sound waves are reflected by the surfaces and interiors of internal organs and structures as "echoes." These echoes return to the transducer and are transmitted onto a viewing monitor. On the monitor, the outline of organs and structures can be determined as well as their consistency, for example, liquid or solid.

Two types of ultrasonographic techniques can be used for diagnosing gallstones:transabdominal ultrasonography and endoscopic ultrasonography.

For transabdominal ultrasonography, the transducer is placed directly on the skin of the abdomen. The sound waves travel through the skin and then into the abdominal organs. Transabdominal ultrasonography is painless, inexpensive, and without risk to the patient. In addition to identifying 97% of gallstones in the gallbladder, abdominal ultrasonography can identify many other abnormalities related to gallstones. It can identify:

Transabdominal ultrasonography also may identify diseases not related to gallstones that may be the cause of the patient's problem, for example, appendicitis. The limitations of transabdominal ultrasonography are that it can only identify gallstones larger than 4-5 millimeters in size, and it is poor at identifying gallstones in the bile ducts.

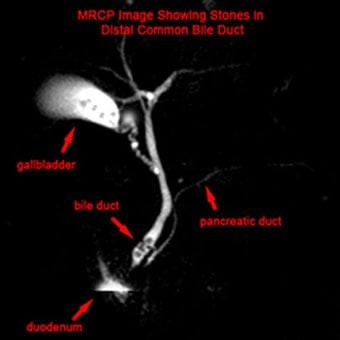

MRCP image showing stones in the common bile duct:(a) Gallbladder with stones (b) Stone in bile duct (c) Pancreatic duct (d) Duodenum.

MRCP image showing stones in the common bile duct:(a) Gallbladder with stones (b) Stone in bile duct (c) Pancreatic duct (d) Duodenum. For endoscopic ultrasonography, a long flexible tube - the endoscope - is swallowed by the patient after he or she has been sedated with intravenous medication. The tip of the endoscope is fitted with an ultrasound transducer. The transducer is advanced into the duodenum where ultrasonographic images are obtained.

Endoscopic ultrasonography can identify gallstones and the same abnormalities as transabdominal ultrasonography; however, since the transducer is much closer to the structures of interest - the gallbladder, bile ducts, and pancreas - better images are obtained than with transabdominal ultrasonography. Thus, it is possible to visualize smaller gallstones with EUS than transabdominal ultrasonography. EUS also is better at identifying gallstones in the common bile duct.

Although endoscopic ultrasonography is in many ways better than transabdominal ultrasonography, it is expensive, not available everywhere, and carries a small risk of complications such as those associated with the use of intravenous sedation, and intestinal perforation by the endoscope. Fortunately, transabdominal ultrasonography usually gives most of the necessary information, and endoscopic ultrasonography is needed only infrequently. Endoscopic ultrasonography also is a better way than transabdominal ultrasonography to evaluate the pancreas for pancreatitis or its complications.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or MRCP is a modification of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that allows the bile and pancreatic ducts to be examined.

The procedure is called cholangitis (referring to the bile ducts) pancreatography (referring to the pancreatic duct) because it can demonstrate the bile and pancreatic ducts.

MRCP has in many instances replaced other procedures such as cholescintigraphy (HIDA scan) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for evaluating the bile ducts. It can identify gallstones in the bile ducts, obstruction of the ducts, and leaks of bile. There are no risks to the patient with MRCP except for very rare reactions to the injected dye.

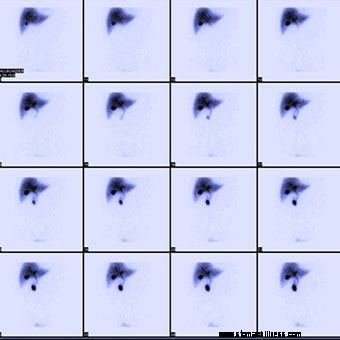

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan) showing a series of scans done over time to see where bile is excreted and/or accumulated.

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan) showing a series of scans done over time to see where bile is excreted and/or accumulated. Cholescintigraphy is a procedure done by nuclear medicine physicians. It also is referred to as a HIDA scan or a gallbladder scan.

HIDA scans are used to identify obstruction of the bile ducts, for example, by a gallstone. They also may identify bile leaks and fistulas. There are no risks to the patient with HIDA scans.

Cholescintigraphy also is used to study the emptying of the gallbladder. Some patients with gallstones have had gallbladder inflammation due to recognized or unrecognized episodes of cholecystitis. (There also are uncommon, non-gallstone-related causes of inflammation of the gallbladder.) The inflammation can result in scarring of the gallbladder's wall and muscle, which reduces the ability of the gallbladder to contract. As a result, the gallbladder does not empty normally. During cholescintigraphy, a synthetic hormone related to cholecystokinin (the hormone the body produces and releases during a meal to cause the gallbladder to contract) can be injected intravenously to cause the gallbladder to contract and squeeze out its bile and radioactivity into the intestine. If the gallbladder does not empty the bile and radioactivity normally, it is assumed that the gallbladder is diseased due to gallstones or non-gallstone-related inflammation.

The problem with interpreting a gallbladder emptying study is that many people with normal gallbladders have abnormal emptying of the gallbladder. Therefore, it is hazardous to base a diagnosis of a diseased gallbladder on abnormal gallbladder emptying alone.

The doctor performs an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on a woman for gallstones.

The doctor performs an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on a woman for gallstones. ERCP is a combined endoscope and X-ray procedure performed to examine the duodenum (the first portion of the small intestine), the papilla of Vater (a small nipple-like structure where the common bile and pancreatic ducts enter the duodenum), the gallbladder, and bile and pancreatic ducts.

The procedure is performed by using a long, flexible, side-viewing instrument (a duodenoscope, a type of endoscope) about the diameter of a fountain pen. The duodenoscope is flexible and can be directed and moved around the many bends of the stomach and intestine. The video-endoscope is the most common type of duodenoscope and uses a chip at the tip of the instrument to transmit video images to a TV screen.

ERCP can identify; 1) gallstones in the gallbladder (though it is not particularly good at this) and 2) blockage of the bile ducts, for example, by gallstones, and 3) bile leaks. ERCP also may identify diseases not related to gallstones that may be the cause of the patient's problem, for example, pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

An important advantage of ERCP is that instruments can be passed through the same channel as the cannula used to inject the dye to extract gallstones stuck in the common and hepatic ducts. This can save the patient from having an operation. ERCP has several risks associated with it, including the drugs used for sedation, perforation of the duodenum by the duodenoscope, and pancreatitis (due to damage to the pancreas). If gallstones are extracted, bleeding also may occur as a complication.

A doctor holding an anatomical model of the human liver and pointing to a gallstone.

A doctor holding an anatomical model of the human liver and pointing to a gallstone. When the liver or pancreas becomes inflamed or their ducts become obstructed and enlarged, the cells of the liver and pancreas release some of their enzymes into the blood. The most commonly measured liver enzymes in blood are aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The most commonly-measured pancreatic enzymes in blood are amylase and lipase. Many medical conditions that affect the liver or pancreas cause these blood tests to become abnormal, so these abnormalities alone cannot be used to diagnose gallstones. Nevertheless, abnormalities of these tests suggest there is a problem with the liver, bile ducts, or pancreas, and gallstones are a common cause of such abnormal tests, particularly during sudden obstruction of the bile ducts or pancreatic ducts. Thus, abnormal liver and pancreatic blood test direct attention to the possibility that gallstones may be causing the acute problem.

Duodenal biliary drainage is a procedure that occasionally can be useful in diagnosing gallstones; however, it is not often used. As previously discussed, gallstones begin as microscopic particles of cholesterol or pigment that grow in size. It is clear that some people who develop biliary colic, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis have only these particles in their gallbladders, yet the particles are too small to obstruct the ducts. There are two potential explanations for how obstruction might occur in this situation. The first is that a small gallstone initially caused an obstruction before passing through the bile ducts into the intestine. The second is that particles passing through the bile ducts can "irritate" the ducts, causing spasm of the muscle within the walls of the ducts (which obstructs the flow of bile) or inflammation of the duct that causes the wall of the duct to swell (which also obstructs the duct).

The risks to the patient of duodenal drainage are minimal. (There have been no reports of reactions to the synthetic hormone.) Nevertheless, duodenal drainage is uncomfortable.

A modification of duodenal drainage involves the collection of bile through an endoscope at the time of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy-either esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or ERCP.

The oral cholecystogram or OCG is a radiologic (X-ray) procedure for diagnosing gallstones.

The OCG is an excellent procedure for diagnosing gallstones; it finds 95% of them. The OCG has been replaced, however, by ultrasonography because ultrasonography is slightly better at finding gallstones and can be done immediately without waiting one or two days for the iodine to be absorbed, excreted, and concentrated.

Unlike ultrasonography, the OCG also cannot give information about the presence of non-gallstone-related diseases. As would be expected, ultrasonography sometimes finds gallstones that are missed by the OCG. Less frequently, the OCG finds gallstones that are missed by ultrasonography. For this reason, if there is a strong suspicion that gallstones are present but ultrasonography does not show them, it is reasonable to consider doing an OCG; however, EUS has mostly replaced the OCG in this situation. An OCG should not be done in individuals who are allergic to iodine.

The intravenous cholangiogram or IVC is a radiologic (X-ray) procedure that is used primarily for looking at the larger intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. It can be used to locate gallstones within these ducts.

An iodine-containing dye is injected intravenously into the blood. The dye is removed from the blood by the liver and excreted into the bile. Unlike the iodine used in the OCG, the iodine in the IVC is concentrated sufficiently enough in the bile ducts to outline the ducts and any gallstones within them. The IVC is rarely used because it has been replaced by MRI cholangiography and endoscopic ultrasound. Moreover, occasional serious reactions to the iodine-containing dye can occur, which rarely may result in the death of the patient.

A senior male patient and doctor. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones.

A senior male patient and doctor. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones. Problems arise, however, because of the high prevalence of silent gallstones and the occasional gallstone that is difficult to diagnose.

If a patient has symptoms that are typical for gallstones, for example, biliary colic, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis, and has gallstones on ultrasonography, little else usually needs to be done to demonstrate that the gallstones are causing the symptoms unless the patient has other complicating medical issues.

If symptoms are not typical for gallstones there is a possibility that the gallstones are innocent bystanders (silent), and most importantly, removing the gallbladder surgically will not resolve the patient's problem or prevent further symptoms. In addition, the real cause of the symptoms will not be pursued. In such a situation, there is a need to obtain further evidence, other than their mere presence, that the gallstones are causing the problem. Such evidence can be obtained during an acute episode or shortly thereafter.

If ultrasonography can be done during an acute episode of pain or inflammation caused by gallstones, it may be possible to demonstrate an enlarged gallbladder or bile duct caused by obstruction of the ducts by the gallstone. This is likely to require ultrasonography again after the episode has resolved in order to demonstrate that the gallbladder indeed was larger during the episode than before or after the episode. It is easier to obtain the necessary ultrasonography if the episode lasts several hours, but it is much more difficult to obtain ultrasonography rapidly enough if the episode lasts only 15 minutes.

Another approach is to test the blood for abnormal liver and pancreatic enzymes. The advantage here is that the enzymes, though not always elevated, can be elevated during an acute attack and for several hours after an episode of gallstone-related pain or inflammation, so they may be abnormal even after the episode has subsided. It is important to remember, however, that the enzymes are not specific for gallstones, and it is necessary to exclude other liver and pancreatic causes for abnormal enzymes.

Sometimes, episodes of pain or inflammation may be more or less typical of gallstones, but transabdominal ultrasonography may not demonstrate either gallstones or another cause of the episodes. In this situation, it is necessary to decide whether the suspicion is high or low for gallstones as a cause of the episodes. If suspicion is low because of lack of typical symptoms, it may be reasonable only to repeat the ultrasonography, possibly obtain an OCG, and/or test for abnormalities of liver or pancreatic enzymes. If suspicion is high because of more typical symptoms, it is reasonable to investigate even further with endoscopic ultrasonography, ERCP, and duodenal drainage. Prior to these "invasive" procedures, some physicians recommend MRCP.

X-Ray during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones, oral dissolution therapy, and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy are some of the treatments.

X-Ray during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones, oral dissolution therapy, and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy are some of the treatments. Most gallstones are silent and do not need treatment.

Cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder surgically) is the standard treatment for gallstones in the gallbladder. Surgery may be done through a large abdominal incision, laparoscopically, or robotically through small punctures in the abdominal wall. Laparoscopic surgery results in less pain and a faster recovery. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery has 3D visualization. Cholecystectomy has a low rate of complications, but serious complications such as damage to the bile ducts and leakage of bile occasionally occur. There also is risk associated with the general anesthesia that is necessary for either type of surgery. Problems following removal of the gallbladder are few. Digestion of food is not affected, and no change in diet is necessary. Nevertheless, chronic diarrhea occurs in approximately 10% of patients.

Sometimes a gallstone may be stuck in the hepatic or common bile ducts. In such situations, there usually are gallstones in the gallbladder as well, and cholecystectomy is necessary. It may be possible to remove the gallstone stuck in the duct at the time of surgery, but this may not always be possible. An alternative means for removing gallstones in the duct before or after cholecystectomy is with sphincterotomy followed by extraction of the gallstone.

Sphincterotomy involves cutting the muscle of the common bile duct (sphincter of Oddi) at the junction of the common bile duct and the duodenum in order to allow easier access to the common bile duct. The cutting is done with an electrosurgical instrument passed through the same type of endoscope that is used for ERCP. After the sphincter is cut, instruments may be passed through the endoscope and into the hepatic and common bile ducts to grab and pull out the gallstone or to crush the gallstone. It also is possible to pass a lithotripsy instrument that uses high-frequency sound waves to break up the gallstone. Complications of sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones include risks associated with general anesthesia, perforation of the bile ducts or duodenum, bleeding, and pancreatitis.

It is possible to dissolve some cholesterol gallstones with medication taken orally. The medication is a naturally occurring bile acid called ursodeoxycholic acid or ursodiol (Actigall, Urso). Bile acids are one of the detergents that the liver secretes into bile to dissolve cholesterol. Although one might expect therapy with ursodiol to work by increasing the number of bile acids in bile and thereby cause the cholesterol in gallstones to dissolve, the mechanism of ursodiol's action actually is different. Ursodiol reduces the amount of cholesterol secreted in bile. The bile then has less cholesterol and becomes capable of dissolving the cholesterol in the gallstones.

There are important limitations to the use of ursodiol:

Due to these limitations, ursodiol generally is used only in individuals with smaller gallstones that are likely to have a very high cholesterol content and who are at high risk for surgery because of ill health. It also is reasonable to use ursodiol in individuals whose gallstones were perhaps formed because of a transient event, for example, the rapid loss of weight, since the gallstones would not be expected to recur following successful dissolution. Another use of ursodiol is to prevent the formation of gallstones in patients who will lose weight rapidly.

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is an infrequently used method for treating gallstones, particularly those lodged in bile ducts. ESWL generators produce shock waves outside of the body that is then focused on the gallstone. The shock waves shatter the gallstone, and the resulting pieces of the gallstone either drain into the intestine on their own or are extracted endoscopically. Shock waves also can be used to break up gallstones via special catheters passed through an endoscope at the time of ERCP.

There are no natural or home remedies to treat gallstones.

A doctor examining a gallstone patient. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones.

A doctor examining a gallstone patient. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones, but, fortunately, it is usually a self-limited symptom. There are, however, more serious complications of gallstones.

Cholecystitis means inflammation of the gallbladder. Like biliary colic, it too is caused by sudden obstruction of the ducts, usually the cystic duct by a gallstone. In fact, cholecystitis may begin with an episode of biliary colic. Obstruction of the cystic duct causes the wall of the gallbladder to begin secreting fluid, but for unclear reasons, inflammation sets in. At first, the inflammation is sterile, that is, there is no infection with bacteria; however, over time the bile and gallbladder become infected with bacteria that travel through the bile ducts from the intestine.

With cholecystitis, there is a constant pain in the right upper abdomen. The inflammation extends through the wall of the gallbladder, and the right upper abdomen becomes particularly tender when it is pressed or even tapped. Unlike with biliary colic, however, it is painful to move around. Individuals with cholecystitis usually lie still. There is fever, and the white blood cell count is elevated, both signs of inflammation. Cholecystitis usually is treated with antibiotics, and most episodes will resolve over several days. Even without antibiotics, cholecystitis often resolves. As with biliary colic, movement of the gallstone out of the cystic duct and back into the gallbladder relieves the obstruction and allows the inflammation to resolve.

Cholangitis is a condition in which bile in the common, hepatic, and intrahepatic ducts becomes infected. Like cholecystitis, the infection spreads through the ducts from the intestine after the ducts become obstructed by a gallstone. Patients with cholangitis are very sick with high fever and elevated white blood cell counts. Cholangitis may result in an abscess within the liver or sepsis. (See the discussion of sepsis that follows.)

Gangrene of the gallbladder is a condition in which the inflammation of cholecystitis cuts off the supply of blood to the gallbladder. Without blood, the tissues forming the wall of the gallbladder die, and this makes the wall very weak. The weakness combined with infection often leads to rupture of the gallbladder. The infection then may spread throughout the abdomen, though often the rupture is confined to a small area around the gallbladder (a confined perforation).

Jaundice is a condition in which bilirubin accumulates in the body. Bilirubin is brownish-black in color but is yellow when it is not too concentrated. A build-up of bilirubin in the body turns the skin and whites of the eye (sclera) yellow. Jaundice occurs when there is prolonged obstruction of the bile ducts. The obstruction may be due to gallstones, but it also may be due to many other causes, for example, tumors of the bile ducts or surrounding tissues. (Other causes of jaundice are rapid destruction of red blood cells that overwhelms the ability of the liver to remove bilirubin from the blood or a damaged liver that cannot remove bilirubin from the blood normally.) Jaundice, by itself, generally does not cause problems.

Pancreatitis means inflammation of the pancreas. The two most common causes of pancreatitis are alcoholism and gallstones. The pancreas surrounds the common bile duct as it enters the intestine. The pancreatic duct that drains the digestive juices from the pancreas joins the common bile duct just before it empties into the intestine. If a gallstone obstructs the common bile duct just after the pancreatic duct joins it, the flow of pancreatic juice from the pancreas is blocked. This results in inflammation within the pancreas. Pancreatitis due to gallstones usually is mild, but it may cause serious illness and even death. Fortunately, severe pancreatitis due to gallstones is rare.

Sepsis is a condition in which bacteria from any source within the body, including the gallbladder or bile ducts, enter into the bloodstream and spread throughout the body. Although the bacteria usually remain within the blood, they also may spread to distant tissues and lead to the formation of abscesses (localized areas of infection with formation of pus). Sepsis is a feared complication of any infection. The signs of sepsis include high fever, high white blood cell count, and, less frequently, rigors (shaking chills) or a drop in blood pressure.

A fistula is an abnormal tract through which fluid can flow between two hollow organs or between an abscess and a hollow organ or skin. Gallstones cause fistulas when the hard gallstone erodes through the soft wall of the gallbladder or bile ducts. Most commonly, the gallstone erodes into the small intestine, stomach, or common bile duct. This can leave a tract that allows bile to flow from the gallbladder to the small intestine, stomach, or the common bile duct. If the fistula enters the distal part of the small intestine, the concentrated bile can lead to problems such as diarrhea. Rarely, the gallstone erodes into the abdominal cavity. The bile then leaks into the abdominal cavity and causes inflammation of the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum), a condition called bile peritonitis.

Ileus is a condition in which there is an obstruction to the flow of food, gas, and liquid within the intestine. It may be due to a mechanical obstruction, for example, a tumor within the intestine, or a functional obstruction, for example, inflammation of the intestine or surrounding tissues that prevents the muscles of the intestine from working normally and propelling intestinal contents. If a large gallstone erodes through the wall of the gallbladder and into the stomach or small intestine, it will be propelled through the small intestine. The narrowest part of the small intestine is the ileocecal valve, which is located at the site where the small intestine joins the colon. If the gallstone is too large to pass through the valve, it can obstruct the small intestine and cause an ileus. Gallstones also may cause ileus if there are other abnormal narrowings in the intestine such as a tumor or scarring.

Cancer of the gallbladder usually is associated with gallstones, but it is not clear which comes first, that is, whether the gallstones precede cancer and, therefore, could potentially be the cause of cancer or the gallstones form because cancer is present. Cancer of the gallbladder arises in less than 1% of individuals with gallstones. Therefore, concern about the future development of cancer is by itself not a good reason for removing the gallbladder when gallstones are present.

Longitudinal and axial scans through the gallbladder show layering of sludge (S) in the gallbladder.

Longitudinal and axial scans through the gallbladder show layering of sludge (S) in the gallbladder. Sludge is a common term that is applied to an abnormality of bile that is seen with ultrasonography of the gallbladder. Specifically, the bile within the gallbladder is seen to be of two different densities with the denser bile on the bottom. The bile is denser because it contains microscopic particles, usually cholesterol or pigment, embedded in mucus. (The mucus is secreted by the gallbladder.) Over time, sludge may remain in the gallbladder, it may disappear and not return, or it may come and go. As discussed previously, these particles may be precursors of gallstones, and they occur often in some situations in which gallstones frequently appear, for example, rapid weight loss, pregnancy, and prolonged fasting.

Nevertheless, it appears that sludge goes on to become gallstones in only a minority of individuals. Just to make matters more difficult, it is not clear how often - if at all - sludge alone causes problems. Sludge has been blamed for many of the same symptoms as gallstones-biliary colic, cholecystitis, and pancreatitis, but often these symptoms and complications are caused by very small gallstones that are missed by ultrasonography. Thus, there is some uncertainty about the importance of sludge.

It is clear, however, that sludge is not the equivalent of gallstones. The practical implication of this uncertainty is that unless an individual's symptoms are typical of gallstones, sludge should not be considered as a possible cause of the symptoms.

Ideally, it would be better if gallstones could be prevented rather than treated. Prevention of cholesterol gallstones is feasible since ursodiol, the bile acid medication that dissolves some cholesterol gallstones, also prevents them from forming. The difficulty is to identify individuals who are at a high risk for developing cholesterol gallstones over a relatively short period of time so that the duration of preventive treatment can be limited. One such group is obese individuals losing weight rapidly with very low calorie diets or with surgery. The risk of gallstones in this group is as high as 40% to 60%. In fact, ursodiol has been shown in several studies to be very effective at preventing gallstones in these individuals. It is important to stress that no dietary changes have been shown to treat or prevent gallstones.

A doctor discusses gallstone prevention and possible after-effects of removal with a patient in the hospital. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones.

A doctor discusses gallstone prevention and possible after-effects of removal with a patient in the hospital. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones. Gallstones usually are diagnosed by a gastroenterologist, a medical subspecialist who deals with diseases of the intestine, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. General surgeons also may be involved in the diagnosis of gallstones but usually are the doctors who treat gallstones because the common treatment is surgical removal of the gallbladder.

It is clear that genetic factors are important in determining who develops gallstones. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones. To date, 8-10 genes have been identified as being associated with cholesterol gallstones, at least in animals that develop cholesterol gallstones. Not surprisingly, the products of many of these genes control the production and secretion (by the liver) of cholesterol, bile acids, and lecithin. The long-term goal is to be able to identify individuals who are genetically at very high risk for cholesterol gallstones and to offer them preventive treatment. An understanding of the exact mechanism(s) of gallstone formation also may result in new therapies for treatment and prevention.

Surgery for gallstones has undergone a major transition from requiring large abdominal incisions to requiring only tiny incisions for laparoscopic instruments (laparoscopic cholecystectomy). It is possible that there will be another transition. Surgeons are experimenting with a technique called natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). NOTES is a new technique for accomplishing standard intra-abdominal surgery, but access to the abdomen is through a natural orifice - the mouth, anus, or vagina.

For NOTES , a flexible endoscopic instrument is similar to the flexible endoscopes presently being used widely is introduced through the chosen orifice, through an incision somewhere inside the orifice (for example, the stomach), and into the abdominal cavity. Thus, the only incision is within the body and not visible on the body's surface. There are potential advantages to this type of surgery, but it is in the early stages of development, and it is unclear what the future role of NOTES will be in gallbladder surgery. Nevertheless, several series of patients have already been described who have had their gallbladders removed via NOTES primarily through the vagina.

Metanógenos:la causa raíz de la hinchazón de la que no ha oído hablar (y una nueva solución para SIBO)

Metanógenos:la causa raíz de la hinchazón de la que no ha oído hablar (y una nueva solución para SIBO)

hacer esta noche:chili con carne apto para sibos

hacer esta noche:chili con carne apto para sibos

Lo que debe saber sobre la disfunción del suelo pélvico

Lo que debe saber sobre la disfunción del suelo pélvico

Cuando alguien a quien amas tiene SII

Cuando alguien a quien amas tiene SII

¿Cómo se trata la insuficiencia velofaríngea?

¿Cómo se trata la insuficiencia velofaríngea?

Las tiopurinas podrían ayudar a detener la replicación viral en coronavirus humanos

Las tiopurinas podrían ayudar a detener la replicación viral en coronavirus humanos

La bacteria Prevotella en la salud del microbioma intestinal, bucal y vaginal

Las prevotella son bacterias que habitan en muchas partes del cuerpo. Aunque son comunes en el microbioma intestinal, si se encuentran en otros lugares, pueden ser un signo de problema o infección.

La bacteria Prevotella en la salud del microbioma intestinal, bucal y vaginal

Las prevotella son bacterias que habitan en muchas partes del cuerpo. Aunque son comunes en el microbioma intestinal, si se encuentran en otros lugares, pueden ser un signo de problema o infección.

¿Debería probar Iberogast para su SII?

Iberogast es una formulación a base de hierbas de venta libre que tiene mucha investigación para respaldar su utilidad para aliviar los síntomas de la dispepsia funcional (FD) y el síndrome del intest

¿Debería probar Iberogast para su SII?

Iberogast es una formulación a base de hierbas de venta libre que tiene mucha investigación para respaldar su utilidad para aliviar los síntomas de la dispepsia funcional (FD) y el síndrome del intest

Qué debe saber sobre Pepcid (famotidina)

Pepcid (famotidina) es un medicamento que se usa para tratar la acidez estomacal, la indigestión y las úlceras gastrointestinales (GI) en niños y adultos. Pepcid reduce la acidez y el volumen del líqu

Qué debe saber sobre Pepcid (famotidina)

Pepcid (famotidina) es un medicamento que se usa para tratar la acidez estomacal, la indigestión y las úlceras gastrointestinales (GI) en niños y adultos. Pepcid reduce la acidez y el volumen del líqu