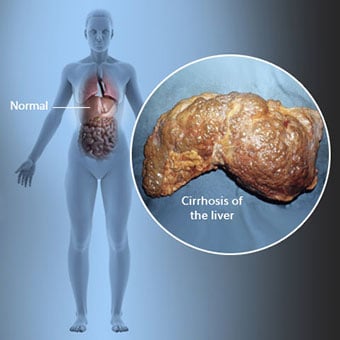

La cirrosis es una complicación de la enfermedad hepática que implica la pérdida de células hepáticas y la cicatrización irreversible del hígado.

La cirrosis es una complicación de la enfermedad hepática que implica la pérdida de células hepáticas y la cicatrización irreversible del hígado. Las personas con cirrosis pueden tener pocos o ningún síntoma y signo de enfermedad hepática. Algunos de los síntomas pueden ser inespecíficos, es decir, no sugieren que el hígado sea su causa. Algunos de los síntomas y signos más comunes de la cirrosis incluyen:

Las personas con cirrosis también desarrollan síntomas y signos a partir de las complicaciones de la cirrosis.

Existen muchas causas de cirrosis, incluidas las sustancias químicas (como el alcohol, las grasas y ciertos medicamentos), los virus, los metales y enfermedad hepática autoinmune en la que el sistema inmunitario del cuerpo ataca al hígado.

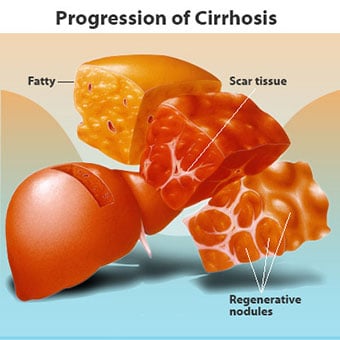

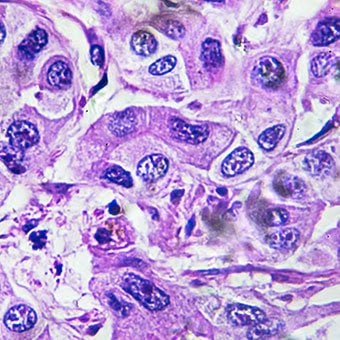

Existen muchas causas de cirrosis, incluidas las sustancias químicas (como el alcohol, las grasas y ciertos medicamentos), los virus, los metales y enfermedad hepática autoinmune en la que el sistema inmunitario del cuerpo ataca al hígado. La cirrosis es una complicación de muchas enfermedades hepáticas caracterizadas por una estructura y función anormales del hígado. Las enfermedades que conducen a la cirrosis lo hacen porque dañan y matan las células del hígado, después de lo cual la inflamación y la reparación asociadas con la muerte de las células del hígado provocan la formación de tejido cicatricial. Las células del hígado que no mueren se multiplican en un intento de reemplazar las células que han muerto. Esto da como resultado grupos de células hepáticas recién formadas (nódulos regenerativos) dentro del tejido cicatricial. Hay muchas causas de cirrosis, incluidas las sustancias químicas (como el alcohol, las grasas y ciertos medicamentos), los virus, los metales tóxicos (como el hierro y el cobre que se acumulan en el hígado como resultado de enfermedades genéticas) y la enfermedad hepática autoinmune en la que el el sistema inmunitario del cuerpo ataca al hígado.

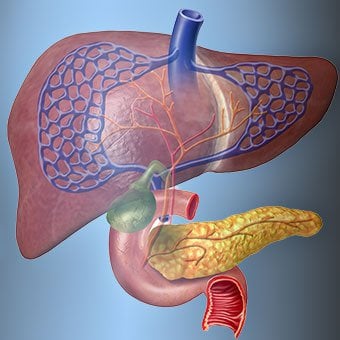

La relación del hígado con la sangre es única.

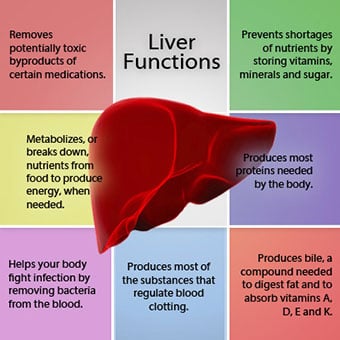

La relación del hígado con la sangre es única. El hígado es un órgano importante en el cuerpo. Realiza muchas funciones críticas, dos de las cuales son la producción de sustancias requeridas por el cuerpo, por ejemplo, la coagulación de proteínas que son necesarias para que la sangre se coagule y la eliminación de sustancias tóxicas que pueden ser dañinas para el cuerpo, por ejemplo, como los medicamentos. . El hígado también tiene un papel importante en la regulación del suministro de glucosa (azúcar) y lípidos (grasa) que el organismo utiliza como combustible. Para realizar estas funciones críticas, las células hepáticas deben funcionar normalmente y deben estar muy cerca de la sangre porque las sustancias que el hígado agrega o elimina son transportadas hacia y desde el hígado por la sangre.

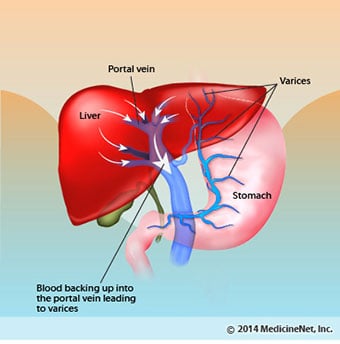

La relación del hígado con la sangre es única. A diferencia de la mayoría de los órganos del cuerpo, las arterias solo suministran una pequeña cantidad de sangre al hígado. La mayor parte del suministro de sangre del hígado proviene de las venas intestinales a medida que la sangre regresa al corazón. La vena principal que devuelve la sangre desde los intestinos se llama vena porta. A medida que la vena porta atraviesa el hígado, se divide en venas cada vez más pequeñas. Las venas más pequeñas (llamadas sinusoides debido a su estructura única) están en estrecho contacto con las células hepáticas. Las células hepáticas se alinean a lo largo de los sinusoides. Esta estrecha relación entre las células del hígado y la sangre de la vena porta permite que las células del hígado eliminen y agreguen sustancias a la sangre. Una vez que la sangre ha pasado por los sinusoides, se recoge en venas cada vez más grandes que finalmente forman una sola vena, la vena hepática, que devuelve la sangre al corazón.

En la cirrosis, se destruye la relación entre la sangre y las células del hígado. Aunque las células hepáticas que sobreviven o se forman recientemente pueden producir y eliminar sustancias de la sangre, no tienen la relación normal e íntima con la sangre, y esto interfiere con la capacidad de las células hepáticas para agregar o eliminar sustancias. de la sangre Además, la cicatrización dentro del hígado cirrótico obstruye el flujo de sangre a través del hígado y hacia las células hepáticas. Como resultado de la obstrucción del flujo de sangre a través del hígado, la sangre "retrocede" en la vena porta y la presión en la vena porta aumenta, una condición llamada hipertensión portal. Debido a la obstrucción del flujo y las altas presiones en la vena porta, la sangre en la vena porta busca otras venas para regresar al corazón, venas con presiones más bajas que evitan el hígado. Desafortunadamente, el hígado no puede agregar o eliminar sustancias de la sangre que lo evitan. Es una combinación de cantidades reducidas de células hepáticas, pérdida del contacto normal entre la sangre que pasa por el hígado y las células hepáticas, y la sangre que pasa por alto el hígado lo que provoca muchos de los signos de cirrosis.

Una segunda razón de los problemas causados por la cirrosis es la relación perturbada entre las células del hígado y los canales a través de los cuales fluye la bilis. La bilis es un líquido producido por las células del hígado que tiene dos funciones importantes:ayudar en la digestión y remover y eliminar sustancias tóxicas del cuerpo. La bilis producida por las células del hígado se secreta en canales muy pequeños que corren entre las células del hígado que recubren los sinusoides, llamados canalículos. Los canalículos desembocan en pequeños conductos que luego se unen para formar conductos cada vez más grandes. Todos los conductos se combinan en un solo conducto que ingresa al intestino delgado, donde puede ayudar con la digestión de los alimentos. Al mismo tiempo, las sustancias tóxicas contenidas en la bilis ingresan al intestino y luego se eliminan en las heces. En la cirrosis, los canalículos son anormales y la relación entre las células hepáticas y los canalículos se destruye, al igual que la relación entre las células hepáticas y la sangre en los sinusoides. Como resultado, el hígado no puede eliminar las sustancias tóxicas normalmente y pueden acumularse en el cuerpo. En menor medida, la digestión en el intestino también se reduce.

Los síntomas y signos comunes de la cirrosis incluyen ictericia, fatiga, debilidad, pérdida de apetito, picazón y moretones con facilidad.

Los síntomas y signos comunes de la cirrosis incluyen ictericia, fatiga, debilidad, pérdida de apetito, picazón y moretones con facilidad. Las personas con cirrosis pueden tener pocos o ningún síntoma y signo de enfermedad hepática. Algunos de los síntomas pueden ser inespecíficos y no sugieren que el hígado sea la causa. Los síntomas y signos comunes de la cirrosis incluyen:

Las personas con cirrosis hepática también desarrollan síntomas y signos a partir de las complicaciones de la enfermedad.

La cirrosis en sí ya es una etapa tardía del daño hepático. En las primeras etapas de la enfermedad hepática habrá inflamación del hígado. Si esta inflamación no se trata, puede provocar cicatrices (fibrosis). En esta etapa, todavía es posible que el hígado sane con tratamiento.

Si la fibrosis del hígado no se trata, puede provocar cirrosis. En esta etapa, el tejido cicatricial no puede sanar, pero la progresión de la cicatrización puede prevenirse o ralentizarse. Las personas con cirrosis que presentan signos de complicaciones pueden desarrollar enfermedad hepática en etapa terminal (ESLD, por sus siglas en inglés) y el único tratamiento en esta etapa es el trasplante de hígado.

Complicaciones de edema, ascitis y peritonitis bacteriana

Complicaciones de edema, ascitis y peritonitis bacteriana A medida que la cirrosis hepática se agrava, se envían señales a los riñones para que retengan sal y agua en el cuerpo. El exceso de sal y agua se acumula primero en el tejido debajo de la piel de los tobillos y las piernas debido al efecto de la gravedad al estar de pie o sentado. Esta acumulación de líquido se denomina edema periférico o edema con fóvea. (El edema con fóvea se refiere al hecho de que presionar con la punta de un dedo firmemente contra un tobillo o una pierna con edema provoca una hendidura en la piel que persiste durante algún tiempo después de liberar la presión. Cualquier tipo de presión, como la de la banda elástica de un calcetín , puede ser suficiente para causar picaduras.) La hinchazón a menudo empeora al final del día después de estar de pie o sentado y puede disminuir durante la noche cuando está acostado. A medida que la cirrosis empeora y se retiene más sal y agua, también se puede acumular líquido en la cavidad abdominal entre la pared abdominal y los órganos abdominales (llamado ascitis), lo que provoca hinchazón del abdomen, malestar abdominal y aumento de peso.

El líquido en la cavidad abdominal (ascitis) es el lugar perfecto para que crezcan las bacterias. Normalmente, la cavidad abdominal contiene una cantidad muy pequeña de líquido que puede resistir bien la infección, y las bacterias que ingresan al abdomen (generalmente desde el intestino) mueren o llegan a la vena porta y al hígado, donde mueren. En la cirrosis, el líquido que se acumula en el abdomen no puede resistir la infección normalmente. Además, más bacterias encuentran su camino desde el intestino hacia la ascitis. Es probable que ocurra una infección dentro del abdomen y la ascitis, llamada peritonitis bacteriana espontánea o PBE. La PBE es una complicación potencialmente mortal. Algunos pacientes con PBE no tienen síntomas, mientras que otros tienen fiebre, escalofríos, dolor y sensibilidad abdominal, diarrea y empeoramiento de la ascitis.

Hemorragia y complicaciones del bazo

Hemorragia y complicaciones del bazo En el hígado cirrótico, el tejido cicatricial bloquea el flujo de sangre que regresa al corazón desde los intestinos y aumenta la presión en la vena porta (hipertensión portal). Cuando la presión en la vena porta aumenta lo suficiente, hace que la sangre fluya alrededor del hígado a través de venas con menor presión para llegar al corazón. Las venas más comunes a través de las cuales la sangre no pasa por el hígado son las venas que recubren la parte inferior del esófago y la parte superior del estómago.

Como resultado del aumento del flujo de sangre y el consiguiente aumento de la presión, las venas en la parte inferior del esófago y la parte superior del estómago se expanden y luego se denominan várices esofágicas y gástricas; cuanto mayor sea la presión portal, más grandes serán las várices y más probabilidades hay de que el paciente sangre de las várices hacia el esófago o el estómago.

El sangrado por várices es severo y sin tratamiento inmediato puede ser fatal. Los síntomas de sangrado por várices incluyen vómitos con sangre (puede aparecer como sangre roja mezclada con coágulos o "posos de café"), heces negras y alquitranadas debido a cambios en la sangre a medida que pasa por el intestino (melena) y ortostática. mareos o desmayos (causados por una caída de la presión arterial, especialmente al ponerse de pie después de estar acostado).

En raras ocasiones, el sangrado puede ocurrir por várices que se forman en otras partes de los intestinos, por ejemplo, el colon. Los pacientes hospitalizados debido a várices esofágicas que sangran activamente tienen un alto riesgo de desarrollar peritonitis bacteriana espontánea, aunque aún no se comprenden las razones de esto.

El bazo normalmente actúa como un filtro para eliminar los glóbulos rojos, los glóbulos blancos y las plaquetas más viejos (pequeñas partículas importantes para la coagulación de la sangre). La sangre que drena del bazo se une a la sangre de los intestinos en la vena porta. A medida que aumenta la presión en la vena porta en la cirrosis, bloquea cada vez más el flujo de sangre desde el bazo. La sangre "retrocede", acumulándose en el bazo, y el bazo aumenta de tamaño, una condición conocida como esplenomegalia. A veces, el bazo está tan agrandado que causa dolor abdominal.

A medida que el bazo se agranda, filtra más y más glóbulos y plaquetas hasta que su número en la sangre se reduce. Hiperesplenismo es el término que se usa para describir esta afección y se asocia con un recuento bajo de glóbulos rojos (anemia), un recuento bajo de glóbulos blancos (leucopenia) y/o un recuento bajo de plaquetas (trombocitopenia). La anemia puede causar debilidad, la leucopenia puede provocar infecciones y la trombocitopenia puede afectar la coagulación de la sangre y provocar un sangrado prolongado

Complicaciones hepáticas (hepáticas)

Complicaciones hepáticas (hepáticas) La cirrosis por cualquier causa aumenta el riesgo de cáncer primario de hígado (carcinoma hepatocelular). Primario se refiere al hecho de que el tumor se origina en el hígado. Un cáncer de hígado secundario es aquel que se origina en otra parte del cuerpo y se disemina (hace metástasis) al hígado.

Los síntomas y signos más comunes del cáncer de hígado primario son dolor e hinchazón abdominales, agrandamiento del hígado, pérdida de peso y fiebre. Además, los cánceres de hígado pueden producir y liberar una serie de sustancias, incluidas las que provocan un aumento en el recuento de glóbulos rojos (eritrocitosis), niveles bajos de azúcar en la sangre (hipoglucemia) y niveles altos de calcio en la sangre (hipercalcemia).

Algunas de las proteínas de los alimentos que escapan a la digestión y la absorción son utilizadas por bacterias que normalmente están presentes en el intestino. Mientras usan la proteína para sus propios fines, las bacterias producen sustancias que liberan en el intestino para luego ser absorbidas por el cuerpo. Algunas de estas sustancias, como el amoníaco, pueden tener efectos tóxicos en el cerebro. Por lo general, estas sustancias tóxicas se transportan desde el intestino en la vena porta hasta el hígado, donde se eliminan de la sangre y se desintoxican.

Cuando hay cirrosis, las células del hígado no pueden funcionar normalmente porque están dañadas o porque han perdido su relación normal con la sangre. Además, parte de la sangre de la vena porta no pasa por el hígado a través de otras venas. El resultado de estas anomalías es que las células hepáticas no pueden eliminar las sustancias tóxicas y, en cambio, se acumulan en la sangre.

Cuando las sustancias tóxicas se acumulan lo suficiente en la sangre, la función del cerebro se ve afectada, una condición llamada encefalopatía hepática. Dormir durante el día en lugar de la noche (inversión del patrón de sueño normal) es un síntoma temprano de encefalopatía hepática. Otros síntomas incluyen irritabilidad, incapacidad para concentrarse o realizar cálculos, pérdida de memoria, confusión o niveles de conciencia deprimidos. En última instancia, la encefalopatía hepática grave provoca el coma y la muerte.

Las sustancias tóxicas también hacen que los cerebros de los pacientes con cirrosis sean muy sensibles a los medicamentos que normalmente el hígado filtra y desintoxica. Es posible que sea necesario reducir las dosis de muchos medicamentos para evitar una acumulación tóxica en la cirrosis, en particular los sedantes y los medicamentos utilizados para promover el sueño. Alternativamente, se pueden usar medicamentos que no necesitan ser desintoxicados o eliminados del cuerpo por el hígado, como los medicamentos eliminados por los riñones.

Los pacientes con empeoramiento de la cirrosis pueden desarrollar síndrome hepatorrenal. Este síndrome es una complicación grave en la que se reduce la función de los riñones. Es un problema funcional en los riñones, lo que significa que no hay daño físico a los riñones. En cambio, la función reducida se debe a cambios en la forma en que la sangre fluye a través de los propios riñones. El síndrome hepatorrenal se define como una falla progresiva de los riñones para eliminar sustancias de la sangre y producir cantidades adecuadas de orina mientras se mantienen otras funciones importantes del riñón, como la retención de sal. Si la función hepática mejora o se trasplanta un hígado sano a un paciente con síndrome hepatorrenal, los riñones suelen volver a funcionar con normalidad. Esto sugiere que la función reducida de los riñones es el resultado de la acumulación de sustancias tóxicas en la sangre o de una función hepática anormal cuando el hígado falla. Hay dos tipos de síndrome hepatorrenal. Un tipo ocurre gradualmente durante meses. El otro ocurre rápidamente en una o dos semanas.

En raras ocasiones, algunos pacientes con cirrosis avanzada pueden desarrollar síndrome hepatopulmonar. Estos pacientes pueden experimentar dificultad para respirar debido a que ciertas hormonas liberadas en la cirrosis avanzada hacen que los pulmones funcionen de manera anormal. El problema básico en el pulmón es que no fluye suficiente sangre a través de los pequeños vasos sanguíneos de los pulmones que están en contacto con los alvéolos (sacos de aire) de los pulmones. La sangre que fluye a través de los pulmones se desvía alrededor de los alvéolos y no puede recoger suficiente oxígeno del aire de los alvéolos. Como resultado, el paciente experimenta dificultad para respirar, especialmente con el esfuerzo.

Hay 12 causas comunes de cirrosis.

Hay 12 causas comunes de cirrosis. Common causes of cirrhosis of the liver include:

Less common causes of cirrhosis include:

In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.

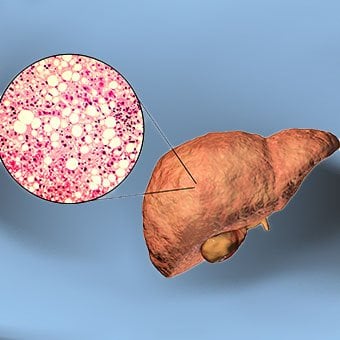

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis. Alcohol is a very common cause of cirrhosis, particularly in the Western world. Chronic, high levels of alcohol consumption injure liver cells. Thirty percent of individuals who drink daily at least eight to sixteen ounces of hard liquor or the equivalent for fifteen or more years will develop cirrhosis. Alcohol causes a range of liver diseases, which include simple and uncomplicated fatty liver (steatosis), more serious fatty liver with inflammation (steatohepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis), and cirrhosis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a wide spectrum of liver diseases that, like alcoholic liver disease, range from simple steatosis, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), to cirrhosis. All stages of NAFLD have in common the accumulation of fat in liver cells. The term nonalcoholic is used because NAFLD occurs in individuals who do not consume excessive amounts of alcohol, yet in many respects the microscopic picture of NAFLD is similar to what can be seen in liver disease that is due to excessive alcohol. NAFLD is associated with a condition called insulin resistance, which, in turn, is associated with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type 2. Obesity is the main cause of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the United States and is responsible for up to 25% of all liver disease. The number of livers transplanted for NAFLD-related cirrhosis is on the rise. Public health officials are worried that the current epidemic of obesity will dramatically increase the development of NAFLD and cirrhosis in the population.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.

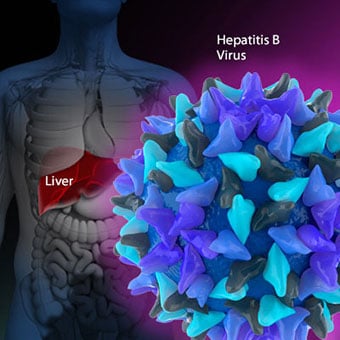

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. Chronic viral hepatitis is a condition in which hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infects the liver for years. Most patients with viral hepatitis will not develop chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. The majority of patients infected with hepatitis A recover completely within weeks, without developing chronic infection. In contrast, some patients infected with hepatitis B virus and most patients infected with hepatitis C virus develop chronic hepatitis, which, in turn, causes progressive liver damage and leads to cirrhosis, and, sometimes, liver cancers.

Autoimmune hepatitis is a liver disease found more commonly in women that is caused by an abnormality of the immune system. The abnormal immune activity in autoimmune hepatitis causes progressive inflammation and destruction of liver cells (hepatocytes), leading ultimately to cirrhosis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. The abnormal immunity in PBC causes chronic inflammation and destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver. The bile ducts are passages within the liver through which bile travels to the intestine. Bile is a fluid produced by the liver that contains substances required for digestion and absorption of fat in the intestine, as well as other compounds that are waste products, such as the pigment bilirubin. (Bilirubin is produced by the breakdown of hemoglobin from old red blood cells.). Along with the gallbladder, the bile ducts make up the biliary tract. In PBC, the destruction of the small bile ducts blocks the normal flow of bile into the intestine. As the inflammation continues to destroy more of the bile ducts, it also spreads to destroy nearby liver cells. As the destruction of the hepatocytes proceeds, scar tissue (fibrosis) forms and spreads throughout the areas of destruction. The combined effects of progressive inflammation, scarring, and the toxic effects of accumulating waste products culminates in cirrhosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an uncommon disease frequently found in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. In PSC, the large bile ducts outside of the liver become inflamed, narrowed, and obstructed. Obstruction to the flow of bile leads to infections of the bile ducts and jaundice, eventually causing cirrhosis. In some patients, injury to the bile ducts (usually because of surgery) also can cause obstruction and cirrhosis of the liver.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. Inherited (genetic) disorders that result in the accumulation of toxic substances in the liver, which leads to tissue damage and cirrhosis. Examples include the abnormal accumulation of iron (hemochromatosis) or copper (Wilson disease). In hemochromatosis, patients inherit a tendency to absorb an excessive amount of iron from food. Over time, iron accumulation in different organs throughout the body causes cirrhosis, arthritis, heart muscle damage leading to heart failure, and testicular dysfunction causing loss of sexual drive. Treatment is aimed at preventing damage to organs by removing iron from the body through phlebotomy (removing blood). In Wilson disease, there is an inherited abnormality in one of the proteins that control copper in the body. Over time, copper accumulates in the liver, eyes, and brain. Cirrhosis, tremor, psychiatric disturbances, and other neurological difficulties occur if the condition is not treated early. Treatment is with oral medication, which increases the amount of copper that is eliminated from the body in the urine.

Cryptogenic cirrhosis (cirrhosis due to unidentified causes) is a common reason for liver transplantation. It is termed called cryptogenic cirrhosis because for many years doctors have been being unable to explain why a proportion of patients developed cirrhosis. Doctors now believe that cryptogenic cirrhosis is due to NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) caused by long-standing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance. The fat in the liver of patients with NASH is believed to disappear with the onset of cirrhosis, and this has made it difficult for doctors to make the connection between NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis for a long time. One important clue that NASH leads to cryptogenic cirrhosis is the finding of a high occurrence of NASH in the new livers of patients undergoing liver transplant for cryptogenic cirrhosis. Finally, a study from France suggests that patients with NASH have a similar risk of developing cirrhosis as patients with long-standing infection with hepatitis C virus. (See discussion that follows.) However, the progression to cirrhosis from NASH is thought to be slow and the diagnosis of cirrhosis typically is made in people in their sixties.

Infants can be born without bile ducts (biliary atresia) and ultimately develop cirrhosis. Other infants are born lacking vital enzymes for controlling sugars that lead to the accumulation of sugars and cirrhosis. On rare occasions, the absence of a specific enzyme can cause cirrhosis and scarring of the lung (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

Less common causes of cirrhosis include unusual reactions to some drugs and prolonged exposure to toxins, as well as chronic heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis). In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. The single best test for diagnosing cirrhosis is a biopsy of the liver. Liver biopsies carry a small risk for serious complications, and biopsy often is reserved for those patients in whom the diagnosis of the type of liver disease or the presence of cirrhosis is not clear. The history, physical examination, or routine testing may suggest the possibility of cirrhosis. If cirrhosis is present, other tests can be used to determine the severity of the cirrhosis and the presence of complications. Tests also may be used to diagnose the underlying disease that is causing the cirrhosis. Examples of how doctors diagnose and evaluate cirrhosis are:

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis. Treatment of cirrhosis includes

Consume a balanced diet and one multivitamin daily. Patients with PBC with impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may need additional vitamins D and K.

Avoid drugs (including alcohol) that cause liver damage. All patients with cirrhosis should avoid alcohol. Most patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis experience an improvement in liver function with abstinence from alcohol. Even patients with chronic hepatitis B and C can substantially reduce liver damage and slow the progression towards cirrhosis with abstinence from alcohol.

Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g., ibuprofen). Patients with cirrhosis can experience worsening of liver and kidney function with NSAIDs.

Eradicate hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus by using anti-viral medications. Not all patients with cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis are candidates for drug treatment. Some patients may experience serious deterioration in liver function and/or intolerable side effects during treatment. Thus, decisions to treat viral hepatitis have to be individualized, after consulting with doctors experienced in treating liver diseases (hepatologists).

Remove blood from patients with hemochromatosis to reduce the levels of iron and prevent further damage to the liver. In Wilson's disease, medications can be used to increase the excretion of copper in the urine to reduce the levels of copper in the body and prevent further damage to the liver.

Suppress the immune system with drugs such as prednisone and azathioprine (Imuran) to decrease inflammation of the liver in autoimmune hepatitis.

Treat patients with PBC with a bile acid preparation, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), also called ursodiol (Actigall). Results of an analysis that combined the results from several clinical trials showed that UDCA increased survival among PBC patients during 4 years of therapy. The development of portal hypertension also was reduced by the UDCA. It is important to note that despite producing clear benefits, UDCA treatment primarily retards progression and does not cure PBC. Other medications such as colchicine and methotrexate also may have benefits in subsets of patients with PBC.

Immunize patients with cirrhosis against infection with hepatitis A and B to prevent a serious deterioration in liver. There are currently no vaccines available for immunizing against hepatitis C.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications. Retaining salt and water can lead to swelling of the ankles and legs (edema) or abdomen (ascites) in patients with cirrhosis. Doctors often advise patients with cirrhosis to restrict dietary salt (sodium) and fluid to decrease edema and ascites. The amount of salt in the diet usually is restricted to 2 grams per day and fluid to 1.2 liters per day. In most patients with cirrhosis, salt and fluid restriction is not enough and diuretics have to be added.

Diuretics are medications that work in the kidneys to promote the elimination of salt and water into the urine. A combination of the diuretics spironolactone (Aldactone) and furosemide (Lasix) can reduce or eliminate the edema and ascites in most patients. During treatment with diuretics, it is important to monitor the function of the kidneys by measuring blood levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine to determine if too much diuretic is being used. Too much diuretic can lead to kidney dysfunction that is reflected in elevations of the BUN and creatinine levels in the blood.

Sometimes, when the diuretics do not work (in which case the ascites is said to be refractory), a long needle or catheter is used to draw out the ascitic fluid directly from the abdomen, a procedure called abdominal paracentesis. It is common to withdraw large amounts (liters) of fluid from the abdomen when the ascites is causing painful abdominal distension and/or difficulty breathing because it limits the movement of the diaphragms.

Another treatment for refractory ascites is a procedure called transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunting (TIPS).

The spleen normally acts as a filter to remove older red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets (small particles important for the clotting of blood). The blood that drains from the spleen joins the blood in the portal vein from the intestines. As the pressure in the portal vein rises in cirrhosis, it increasingly blocks the flow of blood from the spleen. The blood "backs-up," accumulating in the spleen, and the spleen swells in size, a condition referred to as splenomegaly. Sometimes, the spleen is so enlarged it causes abdominal pain.

As the spleen enlarges, it filters out more and more of the blood cells and platelets until their numbers in the blood are reduced. Hypersplenism is the term used to describe this condition, and it is associated with a low red blood cell count (anemia), low white blood cell count (leukopenia), and/or a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). Anemia can cause weakness, leucopenia can lead to infections, and thrombocytopenia can impair the clotting of blood and result in prolonged bleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. If large varices develop in the esophagus or upper stomach, patients with cirrhosis are at risk for serious bleeding due to rupture of these varices. Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. Treatments include medications and procedures to decrease the pressure in the portal vein and procedures to destroy the varices.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Patients with an abnormal sleep cycle, impaired thinking, odd behavior, or other signs of hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Dietary protein is restricted because it is a source of toxic compounds that cause hepatic encephalopathy. Lactulose, which is a liquid, traps toxic compounds in the colon so they cannot be absorbed into the bloodstream, and thus cause encephalopathy. Lactulose is converted to lactic acid in the colon, and the acidic environment that results is believed to trap the toxic compounds produced by the bacteria. To be sure adequate lactulose is present in the colon at all times, the patient should adjust the dose to produce 2 to 3 semiformed bowel movements a day. Lactulose is a laxative, and the effectiveness of treatment can be judged by loosening or increasing the frequency of stools. Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is an antibiotic taken orally that is not absorbed into the body but rather remains in the intestines. It is the preferred mode of treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Antibiotics work by suppressing the bacteria that produce the toxic compounds in the colon.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Patients suspected of having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis usually will undergo paracentesis. The fluid that is removed is examined for white blood cells and cultured for bacteria. Culturing involves inoculating a sample of the ascites into a bottle of nutrient-rich fluid that encourages the growth of bacteria, thus facilitating the identification of even small numbers of bacteria. Blood and urine samples also are often obtained for culturing because many patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis also will have infections in their blood and urine. Many doctors believe the infection may have begun in the blood and the urine and spread to the ascitic fluid to cause spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics such as cefotaxime (Claforan). Patients usually treated with antibiotics include:

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious infection. It often occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis whose immune systems are weak, but with modern antibiotics and early detection and treatment, the prognosis of recovering from an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is good.

In some patients, oral antibiotics (norfloxacin [Noroxin] or sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim [Bactrim]) can be prescribed to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Not all patients with cirrhosis and ascites should be treated with antibiotics to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but some patients are at high risk for developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and warrant preventive treatment.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases. Several types of liver disease that cause cirrhosis (such as hepatitis B and C) are associated with a high incidence of liver cancer. It is useful to screen for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, as early surgical treatment or transplantation of the liver can cure the patient of cancer. The difficulty is that the methods available for screening are only partially effective, identifying at best only half of patients at a curable stage of their cancer. Despite the partial effectiveness of screening, most patients with cirrhosis, particularly hepatitis B and C, are screened yearly or every six months with ultrasound examination of the liver and measurements of cancer-produced proteins in the blood, for example, alpha-fetoprotein.

Cirrhosis is irreversible. Liver function usually gradually worsens despite treatment, and complications of cirrhosis increase and become difficult to treat. When cirrhosis is far advanced liver transplantation often is the only option for treatment. Recent advances in surgical transplantation and medications to prevent infection and rejection of the transplanted liver have greatly improved survival after transplantation. On average, more than 80% of patients who receive transplants are alive after five years. Not everyone with cirrhosis is a candidate for transplantation. Furthermore, there is a shortage of livers to transplant, and they're usually is a long (months to years) wait before a liver for transplanting becomes available. Measures to slow the progression of liver disease, and treat and prevent complications of cirrhosis are vitally important.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

Progress in the management and prevention of cirrhosis continues. Research is ongoing to determine the mechanism of scar formation in the liver and how this process of scarring can be interrupted or even reversed. Newer and better treatments for viral liver disease are being developed to prevent the progression to cirrhosis. Prevention of viral hepatitis by vaccination, which is available for hepatitis B, is being developed for hepatitis C. Treatments for the complications of cirrhosis are being developed or revised, and tested continually. Finally, research is being directed at identifying new proteins in the blood that can detect liver cancer early or predict which patients will develop liver cancer.

28 de julio:Día Mundial contra la Hepatitis

28 de julio:Día Mundial contra la Hepatitis

Estreñimiento

Estreñimiento

COVID-19:cómo se ve la enfermedad

COVID-19:cómo se ve la enfermedad

Dolor de riñón:síntomas, tratamiento y causas

Dolor de riñón:síntomas, tratamiento y causas

Un estudio sugiere un vínculo entre el uso de probióticos y la "confusión cerebral"

Un estudio sugiere un vínculo entre el uso de probióticos y la "confusión cerebral"

Steve's SCD Healing Journal:Semana 26:¡El agua de coco es el Gatorade de la madre naturaleza!

Steve's SCD Healing Journal:Semana 26:¡El agua de coco es el Gatorade de la madre naturaleza!

Pastel de pastor-reimaginado

Ah, Pastor Pastel . El clásico rústico australiano con el que siempre podemos contar. Sin embargo, esta no es una receta cualquiera. Este es su nuevo favorito compatible con SIBO cena, y está lista p

Pastel de pastor-reimaginado

Ah, Pastor Pastel . El clásico rústico australiano con el que siempre podemos contar. Sin embargo, esta no es una receta cualquiera. Este es su nuevo favorito compatible con SIBO cena, y está lista p

Incontinencia intestinal (incontinencia fecal)

Definición de incontinencia intestinal (incontinencia fecal) Imagen de una persona con incontinencia intestinal La incontinencia fecal se puede definir como la pérdida involuntaria de heces (heces)

Incontinencia intestinal (incontinencia fecal)

Definición de incontinencia intestinal (incontinencia fecal) Imagen de una persona con incontinencia intestinal La incontinencia fecal se puede definir como la pérdida involuntaria de heces (heces)

¿Es el síndrome del intestino irritable?

¿Sabía que abril es el Mes de Concientización sobre el Síndrome del Intestino Irritable (SII)? En Ignite, practico principalmente en trastornos intestinales funcionales y otras enfermedades intestina

¿Es el síndrome del intestino irritable?

¿Sabía que abril es el Mes de Concientización sobre el Síndrome del Intestino Irritable (SII)? En Ignite, practico principalmente en trastornos intestinales funcionales y otras enfermedades intestina