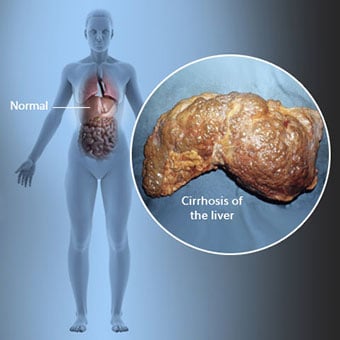

A cirrose é uma complicação da doença hepática que envolve perda de células hepáticas e cicatrização irreversível do fígado.

Cirrose do fígado definição e fatos

- A cirrose é uma complicação da doença hepática que envolve perda de células hepáticas e cicatrização irreversível do fígado.

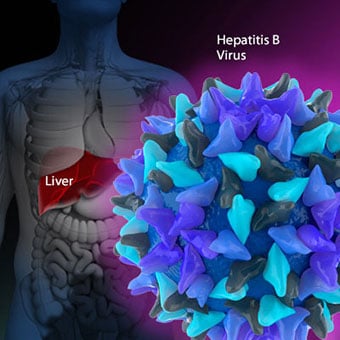

- O álcool e as hepatites virais B e C são causas comuns de cirrose, embora existam muitas outras causas.

- A cirrose pode causar fraqueza, perda de apetite, hematomas fáceis, amarelecimento da pele (icterícia), coceira e fadiga.

- O diagnóstico de cirrose pode ser sugerido pela história, exame físico e exames de sangue, e pode ser confirmado por biópsia hepática.

- As complicações da cirrose incluem:

- Inchaço do abdômen (ascite) e/ou no quadril, coxa, perna, tornozelo e pé

- Peritonite bacteriana espontânea

- Sangramento de varizes

- Encefalopatia hepática

- Síndrome hepatorrenal

- Síndrome hepatopulmonar

- Hipersplenismo

- Câncer de fígado

- O tratamento da cirrose é projetado para evitar mais danos ao fígado, tratar complicações da cirrose e prevenir ou detectar câncer de fígado precocemente.

- O transplante de fígado é uma opção importante para o tratamento de pacientes com cirrose avançada.

- Não há cura para a cirrose hepática e, para algumas pessoas, o prognóstico é ruim. A expectativa de vida para cirrose avançada é de 6 meses a 2 anos, dependendo das complicações da cirrose, e se nenhum doador estiver disponível para transplante de fígado A expectativa de vida para pessoas com cirrose e hepatite acolica pode chegar a 50%.

- A expectativa de vida é de mais de 12 anos para uma pessoa com cirrose e sem complicações maiores.

Sintomas de cirrose do fígado

Indivíduos com cirrose podem ter poucos ou nenhuns sintomas e sinais de doença hepática. Alguns dos sintomas podem ser inespecíficos, ou seja, não sugerem que o fígado seja sua causa. Alguns dos sintomas e sinais mais comuns de cirrose incluem:

- Amarelo da pele (icterícia) devido ao acúmulo de bilirrubina no sangue

- Fadiga

- Fraqueza

- Perda de apetite

- Coceira

- Fácil hematomas devido à diminuição da produção de fatores de coagulação do sangue pelo fígado doente.

Indivíduos com cirrose também desenvolvem sintomas e sinais das complicações da cirrose.

Existem muitas causas de cirrose, incluindo produtos químicos (como álcool, gordura e certos medicamentos), vírus, metais e doença hepática autoimune em que o sistema imunológico do corpo ataca o fígado.

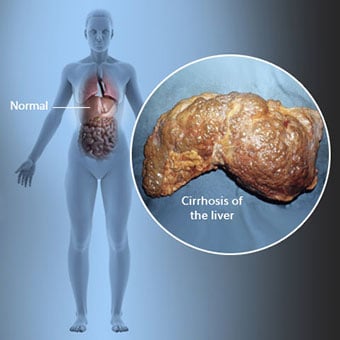

O que é cirrose?

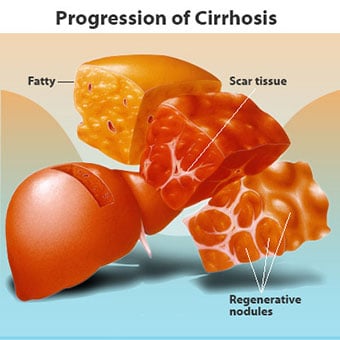

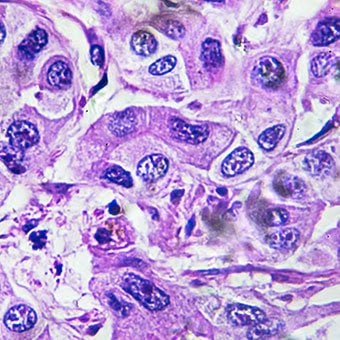

A cirrose é uma complicação de muitas doenças hepáticas caracterizadas por estrutura e função anormais do fígado. As doenças que levam à cirrose fazem isso porque lesam e matam as células do fígado, após o que a inflamação e o reparo associados às células mortas do fígado causam a formação de tecido cicatricial. As células do fígado que não morrem se multiplicam na tentativa de substituir as células que morreram. Isso resulta em aglomerados de células hepáticas recém-formadas (nódulos regenerativos) dentro do tecido cicatricial. Existem muitas causas de cirrose, incluindo produtos químicos (como álcool, gordura e certos medicamentos), vírus, metais tóxicos (como ferro e cobre que se acumulam no fígado como resultado de doenças genéticas) e doença hepática autoimune na qual o o sistema imunológico do corpo ataca o fígado.

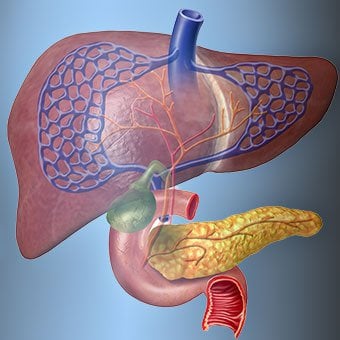

A relação do fígado com o sangue é única.

Por que a cirrose causa problemas?

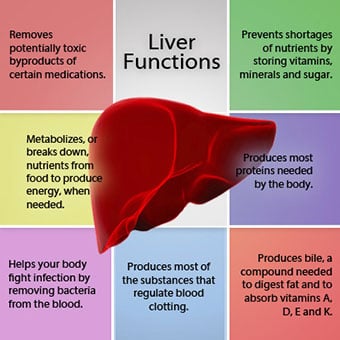

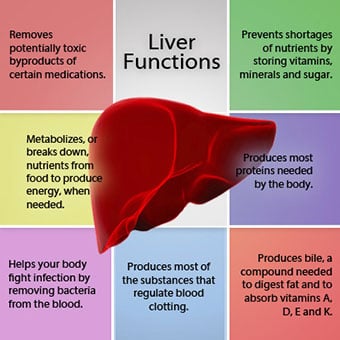

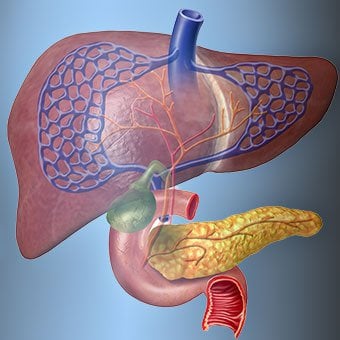

O fígado é um órgão importante no corpo. Desempenha muitas funções críticas, duas das quais são produzir substâncias requeridas pelo corpo, por exemplo, coagular proteínas que são necessárias para que o sangue coagule e remover substâncias tóxicas que podem ser prejudiciais ao corpo, por exemplo, como drogas . O fígado também tem um papel importante na regulação do fornecimento de glicose (açúcar) e lipídios (gordura) que o corpo utiliza como combustível. Para desempenhar essas funções críticas, as células do fígado devem estar funcionando normalmente e devem estar próximas do sangue porque as substâncias que são adicionadas ou removidas pelo fígado são transportadas de e para o fígado pelo sangue.

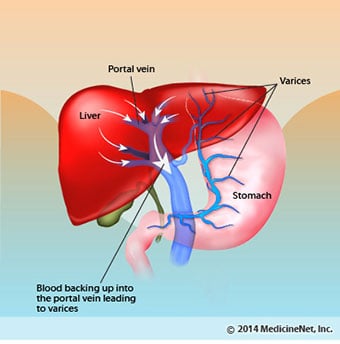

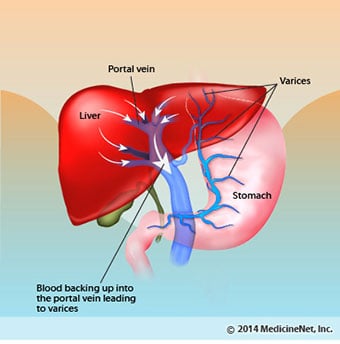

A relação do fígado com o sangue é única. Ao contrário da maioria dos órgãos do corpo, apenas uma pequena quantidade de sangue é fornecida ao fígado pelas artérias. A maior parte do suprimento de sangue do fígado vem das veias intestinais quando o sangue retorna ao coração. A veia principal que retorna o sangue dos intestinos é chamada de veia porta. À medida que a veia porta passa pelo fígado, ela se divide em veias cada vez menores. As veias mais pequenas (chamadas sinusóides devido à sua estrutura única) estão em contato próximo com as células do fígado. As células do fígado se alinham ao longo do comprimento dos sinusóides. Essa estreita relação entre as células do fígado e o sangue da veia porta permite que as células do fígado removam e adicionem substâncias ao sangue. Uma vez que o sangue passou pelos sinusóides, ele é coletado em veias cada vez maiores que acabam por formar uma única veia, a veia hepática, que retorna o sangue ao coração.

Na cirrose, a relação entre o sangue e as células do fígado é destruída. Mesmo que as células do fígado que sobrevivem ou são recém-formadas possam produzir e remover substâncias do sangue, elas não têm uma relação normal e íntima com o sangue, e isso interfere na capacidade das células do fígado de adicionar ou remover substâncias. do sangue. Além disso, a cicatrização no fígado cirrótico obstrui o fluxo de sangue através do fígado e para as células hepáticas. Como resultado da obstrução ao fluxo de sangue através do fígado, o sangue "reflui" na veia porta e a pressão na veia porta aumenta, uma condição chamada hipertensão portal. Devido à obstrução ao fluxo e às altas pressões na veia porta, o sangue na veia porta procura outras veias para retornar ao coração, veias com pressões mais baixas que contornam o fígado. Infelizmente, o fígado é incapaz de adicionar ou remover substâncias do sangue que o ignoram. É uma combinação de números reduzidos de células hepáticas, perda do contato normal entre o sangue que passa pelo fígado e as células do fígado e o sangue que desvia do fígado que leva a muitos dos sinais de cirrose.

Uma segunda razão para os problemas causados pela cirrose é a relação perturbada entre as células do fígado e os canais pelos quais a bile flui. A bile é um fluido produzido pelas células do fígado que tem duas funções importantes:auxiliar na digestão e remover e eliminar substâncias tóxicas do corpo. A bile produzida pelas células do fígado é secretada em canais muito pequenos que correm entre as células do fígado que revestem os sinusóides, chamados canalículos. Os canalículos desembocam em pequenos ductos que se unem para formar ductos cada vez maiores. Todos os dutos se combinam em um duto que entra no intestino delgado, onde pode ajudar na digestão dos alimentos. Ao mesmo tempo, substâncias tóxicas contidas na bile entram no intestino e são eliminadas nas fezes. Na cirrose, os canalículos são anormais e a relação entre as células do fígado e os canalículos é destruída, assim como a relação entre as células do fígado e o sangue nos sinusóides. Como resultado, o fígado não é capaz de eliminar as substâncias tóxicas normalmente, e elas podem se acumular no corpo. Em menor grau, a digestão no intestino também é reduzida.

Os sintomas e sinais comuns de cirrose incluem icterícia, fadiga, fraqueza, perda de apetite, coceira e hematomas fáceis.

Quais são os sinais e sintomas da cirrose?

Pessoas com cirrose podem ter poucos ou nenhum sintoma e sinais de doença hepática. Alguns dos sintomas podem ser inespecíficos e não sugerem que o fígado seja sua causa. Os sintomas e sinais comuns de cirrose incluem:

- Amarelo da pele (icterícia) devido ao acúmulo de bilirrubina no sangue

- Fadiga

- Fraqueza

- Perda de apetite

- Coceira

- Fácil hematomas devido à diminuição da produção de fatores de coagulação do sangue pelo fígado doente.

Pessoas com cirrose hepática também desenvolvem sintomas e sinais das complicações da doença.

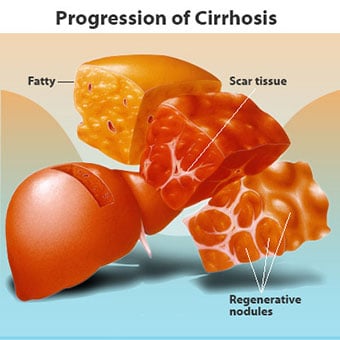

Quais são os estágios da cirrose hepática?

A cirrose em si já é um estágio tardio de dano hepático. Nos estágios iniciais da doença hepática, haverá inflamação do fígado. Se esta inflamação não for tratada, pode levar a cicatrizes (fibrose). Nesta fase, ainda é possível que o fígado se cure com o tratamento.

Se a fibrose do fígado não for tratada, pode resultar em cirrose. Nesta fase, o tecido cicatricial não pode cicatrizar, mas a progressão da cicatrização pode ser prevenida ou retardada. Pessoas com cirrose que apresentam sinais de complicações podem desenvolver doença hepática terminal (ESLD) e o único tratamento neste estágio é o transplante de fígado.

- Cirrose estágio 1 envolve algumas cicatrizes do fígado, mas poucos sintomas. Esta fase é considerada cirrose compensada, onde não há complicações.

- Cirrose estágio 2 inclui o agravamento da hipertensão portal e o desenvolvimento de varizes.

- Cirrose estágio 3 envolve o desenvolvimento de inchaço no abdômen e cicatrização avançada do fígado. Esta fase marca a cirrose descompensada, com complicações graves e possível insuficiência hepática.

- Cirrose estágio 4 pode ser fatal e as pessoas desenvolvem doença hepática em estágio terminal (ESLD), que é fatal sem transplante.

Edema, ascite e complicações de peritonite bacteriana

Edema, ascite e peritonite bacteriana complicações da cirrose

Edema e ascite

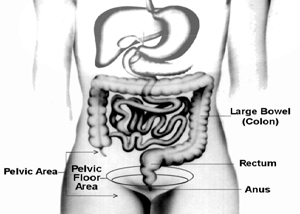

À medida que a cirrose do fígado se torna grave, os sinais são enviados aos rins para reter sal e água no corpo. O excesso de sal e água acumula-se primeiro no tecido sob a pele dos tornozelos e pernas devido ao efeito da gravidade quando em pé ou sentado. Esse acúmulo de líquido é chamado de edema periférico ou edema depressível. (Edema depressível refere-se ao fato de que pressionar a ponta do dedo firmemente contra um tornozelo ou perna com edema causa uma reentrância na pele que persiste por algum tempo após a liberação da pressão. Qualquer tipo de pressão, como o elástico de uma meia , pode ser suficiente para causar depressões.) O inchaço geralmente é pior no final de um dia depois de ficar de pé ou sentado e pode diminuir durante a noite quando deitado. À medida que a cirrose piora e mais sal e água são retidos, o líquido também pode se acumular na cavidade abdominal entre a parede abdominal e os órgãos abdominais (chamado ascite), causando inchaço do abdômen, desconforto abdominal e aumento de peso.

Peritonite bacteriana espontânea (SBP)

O fluido na cavidade abdominal (ascite) é o local perfeito para o crescimento de bactérias. Normalmente, a cavidade abdominal contém uma quantidade muito pequena de fluido que pode resistir bem à infecção, e as bactérias que entram no abdômen (geralmente do intestino) são mortas ou encontram seu caminho para a veia porta e para o fígado, onde são mortas. Na cirrose, o fluido que se acumula no abdômen é incapaz de resistir à infecção normalmente. Além disso, mais bactérias encontram seu caminho do intestino para a ascite. É provável que ocorra infecção no abdômen e na ascite, chamada peritonite bacteriana espontânea ou PBE. A PAS é uma complicação com risco de vida. Alguns pacientes com PBE não apresentam sintomas, enquanto outros apresentam febre, calafrios, dor e sensibilidade abdominal, diarreia e piora da ascite.

Sangramento e complicações do baço

Sangramento e complicações do baço da cirrose

Sangramento de varizes esofágicas

No fígado cirrótico, o tecido cicatricial bloqueia o fluxo de sangue que retorna ao coração dos intestinos e aumenta a pressão na veia porta (hipertensão portal). Quando a pressão na veia porta se torna alta o suficiente, faz com que o sangue flua ao redor do fígado através das veias com pressão mais baixa para chegar ao coração. As veias mais comuns através das quais o sangue desvia do fígado são as veias que revestem a parte inferior do esôfago e a parte superior do estômago.

Como resultado do aumento do fluxo sanguíneo e do consequente aumento da pressão, as veias do esôfago inferior e do estômago superior se expandem e são chamadas de varizes esofágicas e gástricas; quanto maior a pressão portal, maiores as varizes e maior a probabilidade de um paciente sangrar das varizes para o esôfago ou estômago.

O sangramento de varizes é grave e sem tratamento imediato pode ser fatal. Os sintomas de sangramento de varizes incluem vômitos com sangue (pode aparecer como sangue vermelho misturado com coágulos ou "borra de café"), fezes pretas e alcatroadas devido a alterações no sangue ao passar pelo intestino (melena) e ortostatismo tonturas ou desmaios (causados por uma queda na pressão arterial, especialmente ao se levantar de uma posição deitada).

Raramente pode ocorrer sangramento de varizes que se formam em outras partes do intestino, por exemplo, no cólon. Pacientes hospitalizados por causa de varizes esofágicas com sangramento ativo têm alto risco de desenvolver peritonite bacteriana espontânea, embora as razões para isso ainda não sejam compreendidas.

Hipersplenismo

O baço normalmente atua como um filtro para remover os glóbulos vermelhos mais velhos, glóbulos brancos e plaquetas (pequenas partículas importantes para a coagulação do sangue). O sangue que drena do baço junta-se ao sangue na veia porta dos intestinos. À medida que a pressão na veia porta aumenta na cirrose, ela bloqueia cada vez mais o fluxo de sangue do baço. O sangue "retorna", acumulando-se no baço, e o baço aumenta de tamanho, uma condição conhecida como esplenomegalia. Às vezes, o baço está tão aumentado que causa dor abdominal.

À medida que o baço aumenta, ele filtra cada vez mais células sanguíneas e plaquetas até que seus números no sangue sejam reduzidos. O hiperesplenismo é o termo usado para descrever essa condição e está associado a uma baixa contagem de glóbulos vermelhos (anemia), baixa contagem de glóbulos brancos (leucopenia) e/ou baixa contagem de plaquetas (trombocitopenia). A anemia pode causar fraqueza, a leucopenia pode levar a infecções e a trombocitopenia pode prejudicar a coagulação do sangue e resultar em sangramento prolongado

Complicações hepáticas (hepáticas)

Complicações hepáticas (hepáticas) da cirrose

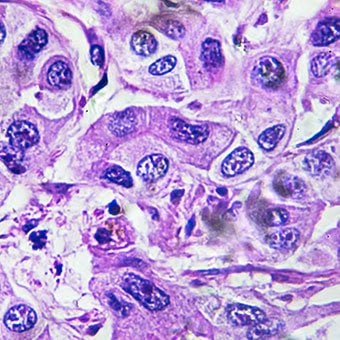

Câncer de fígado (carcinoma hepatocelular)

A cirrose por qualquer causa aumenta o risco de câncer primário de fígado (carcinoma hepatocelular). Primário refere-se ao fato de que o tumor se origina no fígado. Um câncer de fígado secundário é aquele que se origina em outras partes do corpo e se espalha (metástase) para o fígado.

Os sintomas e sinais mais comuns de câncer de fígado primário são dor e inchaço abdominal, aumento do tamanho do fígado, perda de peso e febre. Além disso, os cânceres de fígado podem produzir e liberar várias substâncias, incluindo aquelas que causam um aumento na contagem de glóbulos vermelhos (eritrocitose), baixo nível de açúcar no sangue (hipoglicemia) e alto nível de cálcio no sangue (hipercalcemia).

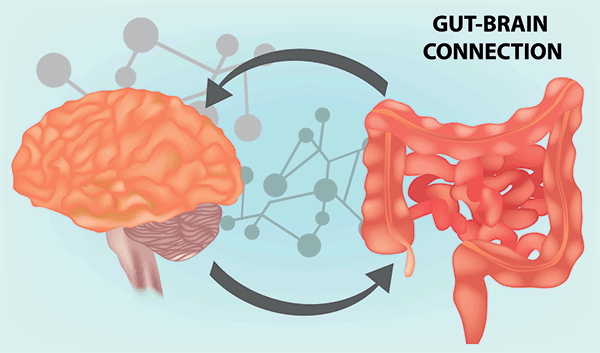

Encefalopatia hepática

Algumas das proteínas dos alimentos que escapam à digestão e absorção são usadas por bactérias que normalmente estão presentes no intestino. Ao usar a proteína para seus próprios propósitos, as bactérias produzem substâncias que liberam no intestino para serem absorvidas pelo corpo. Algumas dessas substâncias, como a amônia, podem ter efeitos tóxicos no cérebro. Normalmente, essas substâncias tóxicas são transportadas do intestino pela veia porta para o fígado, onde são removidas do sangue e desintoxicadas.

Quando a cirrose está presente, as células do fígado não podem funcionar normalmente porque estão danificadas ou porque perderam sua relação normal com o sangue. Além disso, parte do sangue na veia porta desvia-se do fígado através de outras veias. O resultado dessas anormalidades é que as substâncias tóxicas não podem ser removidas pelas células do fígado e, em vez disso, se acumulam no sangue.

Quando as substâncias tóxicas se acumulam suficientemente no sangue, a função do cérebro é prejudicada, uma condição chamada encefalopatia hepática. Dormir durante o dia e não à noite (reversão do padrão de sono normal) é um sintoma precoce de encefalopatia hepática. Outros sintomas incluem irritabilidade, incapacidade de se concentrar ou realizar cálculos, perda de memória, confusão ou níveis deprimidos de consciência. Em última análise, a encefalopatia hepática grave causa coma e morte.

As substâncias tóxicas também tornam os cérebros dos pacientes com cirrose muito sensíveis a drogas que normalmente são filtradas e desintoxicadas pelo fígado. As doses de muitos medicamentos podem ter que ser reduzidas para evitar um acúmulo tóxico na cirrose, particularmente sedativos e medicamentos usados para promover o sono. Alternativamente, podem ser usados medicamentos que não precisam ser desintoxicados ou eliminados do corpo pelo fígado, como os medicamentos eliminados pelos rins.

Síndrome hepatorrenal

Pacientes com piora da cirrose podem desenvolver síndrome hepatorrenal. Esta síndrome é uma complicação grave em que a função dos rins é reduzida. É um problema funcional nos rins, o que significa que não há danos físicos aos rins. Em vez disso, a função reduzida é devido a mudanças na maneira como o sangue flui pelos próprios rins. A síndrome hepatorrenal é definida como uma falha progressiva dos rins em eliminar substâncias do sangue e produzir quantidades adequadas de urina, enquanto outras funções importantes do rim, como a retenção de sal, são mantidas. Se a função hepática melhorar ou um fígado saudável for transplantado para um paciente com síndrome hepatorrenal, os rins geralmente começam a funcionar normalmente novamente. Isso sugere que a função reduzida dos rins é o resultado do acúmulo de substâncias tóxicas no sangue ou da função hepática anormal quando o fígado falha. Existem dois tipos de síndrome hepatorrenal. Um tipo ocorre gradualmente ao longo de meses. O outro ocorre rapidamente ao longo de uma semana ou duas.

Síndrome hepatopulmonar

Raramente, alguns pacientes com cirrose avançada podem desenvolver síndrome hepatopulmonar. Esses pacientes podem sentir dificuldade em respirar porque certos hormônios liberados na cirrose avançada fazem com que os pulmões funcionem de forma anormal. O problema básico no pulmão é que não há fluxo suficiente de sangue através dos pequenos vasos sanguíneos nos pulmões que estão em contato com os alvéolos (sacos aéreos) dos pulmões. O sangue que flui pelos pulmões é desviado ao redor dos alvéolos e não consegue captar oxigênio suficiente do ar nos alvéolos. Como resultado, o paciente sente falta de ar, principalmente com esforço.

Existem 12 causas comuns de cirrose.

Quais são as causas comuns de cirrose?

Causas comuns de cirrose do fígado incluem:

- Álcool

- Doença hepática gordurosa não alcoólica

- Causas criptogênicas

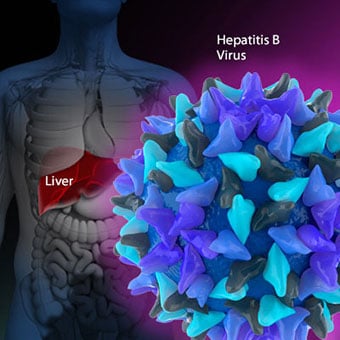

- Hepatite viral crônica (A, B e C)

- Hepatite autoimune

- Inherited (genetic) disorders

- Primary biliary cirrhosis (PCB)

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

- Infants born without bile ducts

Less common causes of cirrhosis include:

- Unusual reactions to some drugs

- Prolonged exposure to toxins

- Chronic heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis).

In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Alcohol

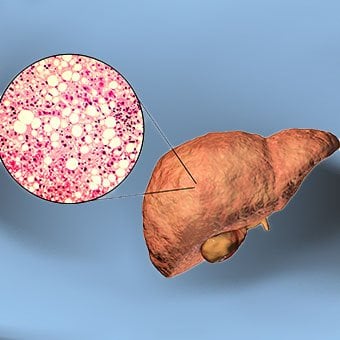

Alcohol is a very common cause of cirrhosis, particularly in the Western world. Chronic, high levels of alcohol consumption injure liver cells. Thirty percent of individuals who drink daily at least eight to sixteen ounces of hard liquor or the equivalent for fifteen or more years will develop cirrhosis. Alcohol causes a range of liver diseases, which include simple and uncomplicated fatty liver (steatosis), more serious fatty liver with inflammation (steatohepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis), and cirrhosis.

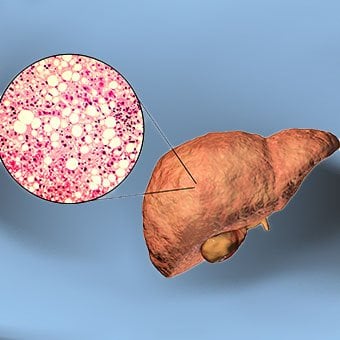

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a wide spectrum of liver diseases that, like alcoholic liver disease, range from simple steatosis, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), to cirrhosis. All stages of NAFLD have in common the accumulation of fat in liver cells. The term nonalcoholic is used because NAFLD occurs in individuals who do not consume excessive amounts of alcohol, yet in many respects the microscopic picture of NAFLD is similar to what can be seen in liver disease that is due to excessive alcohol. NAFLD is associated with a condition called insulin resistance, which, in turn, is associated with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type 2. Obesity is the main cause of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the United States and is responsible for up to 25% of all liver disease. The number of livers transplanted for NAFLD-related cirrhosis is on the rise. Public health officials are worried that the current epidemic of obesity will dramatically increase the development of NAFLD and cirrhosis in the population.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.

Hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis

Chronic viral hepatitis (hep B and C)

Chronic viral hepatitis is a condition in which hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infects the liver for years. Most patients with viral hepatitis will not develop chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. The majority of patients infected with hepatitis A recover completely within weeks, without developing chronic infection. In contrast, some patients infected with hepatitis B virus and most patients infected with hepatitis C virus develop chronic hepatitis, which, in turn, causes progressive liver damage and leads to cirrhosis, and, sometimes, liver cancers.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is a liver disease found more commonly in women that is caused by an abnormality of the immune system. The abnormal immune activity in autoimmune hepatitis causes progressive inflammation and destruction of liver cells (hepatocytes), leading ultimately to cirrhosis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. The abnormal immunity in PBC causes chronic inflammation and destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver. The bile ducts are passages within the liver through which bile travels to the intestine. Bile is a fluid produced by the liver that contains substances required for digestion and absorption of fat in the intestine, as well as other compounds that are waste products, such as the pigment bilirubin. (Bilirubin is produced by the breakdown of hemoglobin from old red blood cells.). Along with the gallbladder, the bile ducts make up the biliary tract. In PBC, the destruction of the small bile ducts blocks the normal flow of bile into the intestine. As the inflammation continues to destroy more of the bile ducts, it also spreads to destroy nearby liver cells. As the destruction of the hepatocytes proceeds, scar tissue (fibrosis) forms and spreads throughout the areas of destruction. The combined effects of progressive inflammation, scarring, and the toxic effects of accumulating waste products culminates in cirrhosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an uncommon disease frequently found in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. In PSC, the large bile ducts outside of the liver become inflamed, narrowed, and obstructed. Obstruction to the flow of bile leads to infections of the bile ducts and jaundice, eventually causing cirrhosis. In some patients, injury to the bile ducts (usually because of surgery) also can cause obstruction and cirrhosis of the liver.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Inherited disorders, cryptogenic cirrhosis, and biliary atresia in infants

Inherited (genetic) disorders

Inherited (genetic) disorders that result in the accumulation of toxic substances in the liver, which leads to tissue damage and cirrhosis. Examples include the abnormal accumulation of iron (hemochromatosis) or copper (Wilson disease). In hemochromatosis, patients inherit a tendency to absorb an excessive amount of iron from food. Over time, iron accumulation in different organs throughout the body causes cirrhosis, arthritis, heart muscle damage leading to heart failure, and testicular dysfunction causing loss of sexual drive. Treatment is aimed at preventing damage to organs by removing iron from the body through phlebotomy (removing blood). In Wilson disease, there is an inherited abnormality in one of the proteins that control copper in the body. Over time, copper accumulates in the liver, eyes, and brain. Cirrhosis, tremor, psychiatric disturbances, and other neurological difficulties occur if the condition is not treated early. Treatment is with oral medication, which increases the amount of copper that is eliminated from the body in the urine.

Cryptogenic cirrhosis

Cryptogenic cirrhosis (cirrhosis due to unidentified causes) is a common reason for liver transplantation. It is termed called cryptogenic cirrhosis because for many years doctors have been being unable to explain why a proportion of patients developed cirrhosis. Doctors now believe that cryptogenic cirrhosis is due to NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) caused by long-standing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance. The fat in the liver of patients with NASH is believed to disappear with the onset of cirrhosis, and this has made it difficult for doctors to make the connection between NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis for a long time. One important clue that NASH leads to cryptogenic cirrhosis is the finding of a high occurrence of NASH in the new livers of patients undergoing liver transplant for cryptogenic cirrhosis. Finally, a study from France suggests that patients with NASH have a similar risk of developing cirrhosis as patients with long-standing infection with hepatitis C virus. (See discussion that follows.) However, the progression to cirrhosis from NASH is thought to be slow and the diagnosis of cirrhosis typically is made in people in their sixties.

Biliary atresia

Infants can be born without bile ducts (biliary atresia) and ultimately develop cirrhosis. Other infants are born lacking vital enzymes for controlling sugars that lead to the accumulation of sugars and cirrhosis. On rare occasions, the absence of a specific enzyme can cause cirrhosis and scarring of the lung (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

Less common causes of cirrhosis include unusual reactions to some drugs and prolonged exposure to toxins, as well as chronic heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis). In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

How is cirrhosis diagnosed and evaluated?

The single best test for diagnosing cirrhosis is a biopsy of the liver. Liver biopsies carry a small risk for serious complications, and biopsy often is reserved for those patients in whom the diagnosis of the type of liver disease or the presence of cirrhosis is not clear. The history, physical examination, or routine testing may suggest the possibility of cirrhosis. If cirrhosis is present, other tests can be used to determine the severity of the cirrhosis and the presence of complications. Tests also may be used to diagnose the underlying disease that is causing the cirrhosis. Examples of how doctors diagnose and evaluate cirrhosis are:

- The patient's history. The doctor may uncover a history of excessive and prolonged intake of alcohol, a history of intravenous drug abuse, or a history of hepatitis. This can suggest the possibility of liver disease and cirrhosis.

- Patients who are known to have chronic viral hepatitis B or C have a higher probability of having cirrhosis.

- Some patients with cirrhosis have enlarged livers and/or spleens. A doctor can often feel (palpate) the lower edge of an enlarged liver below the right rib cage and feel the tip of the enlarged spleen below the left rib cage. A cirrhotic liver also feels firmer and more irregular than a normal liver.

- Some patients with cirrhosis, particularly alcoholic cirrhosis, have small red spider-like markings (telangiectasias) on the skin, particularly on the chest that are made up of enlarged, radiating blood vessels. However, these spider telangiectasias also can be seen in individuals without liver disease.

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes due to elevated bilirubin in the blood) is common among patients with cirrhosis, but jaundice can occur in patients with liver diseases without cirrhosis and other conditions such as hemolysis (excessive break down of red blood cells).

- Swelling of the abdomen (ascites) and/or the lower extremities (edema) due to retention of fluid is common among patients with cirrhosis, although other diseases can cause them commonly, for example, congestive heart failure.

- Patients with abnormal copper deposits in their eyes or certain types of neurologic disease may have Wilson disease, a genetic disease in which there are abnormal handling and accumulation of copper throughout the body, including the liver, which can lead to cirrhosis.

- Esophageal varices may be found unexpectedly during upper endoscopy (EGD), strongly suggesting cirrhosis.

- Computerized tomography (CT or CAT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and ultrasound examinations of the abdomen done for reasons other than evaluating the possibility of liver disease may unexpectedly detect enlarged livers, abnormally nodular livers, enlarged spleens, and fluid in the abdomen, which suggest cirrhosis.

- Advanced cirrhosis leads to a reduced level of albumin in the blood and reduced blood clotting factors due to the loss of the liver's ability to produce these proteins. Reduced levels of albumin in the blood or abnormal bleeding suggest cirrhosis.

- An abnormal elevation of liver enzymes in the blood (such as ALT and AST) that are obtained routinely as part of yearly health examinations suggests inflammation or injury to the liver from many causes as well as cirrhosis.

- Patients with elevated levels of iron in their blood may have hemochromatosis, a genetic disease of the liver in which iron is handled abnormally and which leads to cirrhosis.

- Autoantibodies (antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and anti-mitochondrial antibody) sometimes are detected in the blood and maybe a clue to the presence of autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis, both of which can lead to cirrhosis.

- Liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) may be detected by CT and MRI scans or ultrasound of the abdomen. Liver cancer most commonly develops in individuals with underlying cirrhosis.

- Elevation of tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein suggests the presence of liver cancer.

- If there is an accumulation of fluid in the abdomen, a sample of the fluid can be removed using a long needle to be examined and tested. The results of testing may suggest the presence of cirrhosis as the cause of the fluid.

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.

What are treatment options for cirrhosis?

Treatment of cirrhosis includes

- preventing further damage to the liver,

- treating the complications of cirrhosis,

- preventing liver cancer or detecting it early, and

- liver transplantation.

Preventing further damage to the liver

Consume a balanced diet and one multivitamin daily. Patients with PBC with impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may need additional vitamins D and K.

Avoid drugs (including alcohol) that cause liver damage. All patients with cirrhosis should avoid alcohol. Most patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis experience an improvement in liver function with abstinence from alcohol. Even patients with chronic hepatitis B and C can substantially reduce liver damage and slow the progression towards cirrhosis with abstinence from alcohol.

Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g., ibuprofen). Patients with cirrhosis can experience worsening of liver and kidney function with NSAIDs.

Eradicate hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus by using anti-viral medications. Not all patients with cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis are candidates for drug treatment. Some patients may experience serious deterioration in liver function and/or intolerable side effects during treatment. Thus, decisions to treat viral hepatitis have to be individualized, after consulting with doctors experienced in treating liver diseases (hepatologists).

Remove blood from patients with hemochromatosis to reduce the levels of iron and prevent further damage to the liver. In Wilson's disease, medications can be used to increase the excretion of copper in the urine to reduce the levels of copper in the body and prevent further damage to the liver.

Suppress the immune system with drugs such as prednisone and azathioprine (Imuran) to decrease inflammation of the liver in autoimmune hepatitis.

Treat patients with PBC with a bile acid preparation, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), also called ursodiol (Actigall). Results of an analysis that combined the results from several clinical trials showed that UDCA increased survival among PBC patients during 4 years of therapy. The development of portal hypertension also was reduced by the UDCA. It is important to note that despite producing clear benefits, UDCA treatment primarily retards progression and does not cure PBC. Other medications such as colchicine and methotrexate also may have benefits in subsets of patients with PBC.

Immunize patients with cirrhosis against infection with hepatitis A and B to prevent a serious deterioration in liver. There are currently no vaccines available for immunizing against hepatitis C.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.

Treatment for edema, acites, and hypersplenism complications

Edema and ascites

Retaining salt and water can lead to swelling of the ankles and legs (edema) or abdomen (ascites) in patients with cirrhosis. Doctors often advise patients with cirrhosis to restrict dietary salt (sodium) and fluid to decrease edema and ascites. The amount of salt in the diet usually is restricted to 2 grams per day and fluid to 1.2 liters per day. In most patients with cirrhosis, salt and fluid restriction is not enough and diuretics have to be added.

Diuretics are medications that work in the kidneys to promote the elimination of salt and water into the urine. A combination of the diuretics spironolactone (Aldactone) and furosemide (Lasix) can reduce or eliminate the edema and ascites in most patients. During treatment with diuretics, it is important to monitor the function of the kidneys by measuring blood levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine to determine if too much diuretic is being used. Too much diuretic can lead to kidney dysfunction that is reflected in elevations of the BUN and creatinine levels in the blood.

Sometimes, when the diuretics do not work (in which case the ascites is said to be refractory), a long needle or catheter is used to draw out the ascitic fluid directly from the abdomen, a procedure called abdominal paracentesis. It is common to withdraw large amounts (liters) of fluid from the abdomen when the ascites is causing painful abdominal distension and/or difficulty breathing because it limits the movement of the diaphragms.

Another treatment for refractory ascites is a procedure called transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunting (TIPS).

Hypersplenism

The spleen normally acts as a filter to remove older red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets (small particles important for the clotting of blood). The blood that drains from the spleen joins the blood in the portal vein from the intestines. As the pressure in the portal vein rises in cirrhosis, it increasingly blocks the flow of blood from the spleen. The blood "backs-up," accumulating in the spleen, and the spleen swells in size, a condition referred to as splenomegaly. Sometimes, the spleen is so enlarged it causes abdominal pain.

As the spleen enlarges, it filters out more and more of the blood cells and platelets until their numbers in the blood are reduced. Hypersplenism is the term used to describe this condition, and it is associated with a low red blood cell count (anemia), low white blood cell count (leukopenia), and/or a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). Anemia can cause weakness, leucopenia can lead to infections, and thrombocytopenia can impair the clotting of blood and result in prolonged bleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.

Treatment for bleeding from varices complications

If large varices develop in the esophagus or upper stomach, patients with cirrhosis are at risk for serious bleeding due to rupture of these varices. Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. Treatments include medications and procedures to decrease the pressure in the portal vein and procedures to destroy the varices.

- Propranolol (Inderal), a beta-blocker, is effective in lowering the pressure in the portal vein and is used to prevent initial bleeding and rebleeding from varices in patients with cirrhosis. Another class of oral medications that lower portal pressure is nitrates, such as isosorbide dinitrate (Isordil). Nitrates often are added to propranolol if propranolol alone does not adequately lower portal pressure or prevent bleeding.

- Octreotide (Sandostatin) also decreases portal vein pressure and has been used to treat variceal bleeding.

- During upper endoscopy (EGD) sclerotherapy or band ligation can be performed to obliterate varices, stop active bleeding, and prevent rebleeding. Sclerotherapy is less commonly used due to a higher risk of complications as compared to band ligation. Band ligation involves applying rubber bands around the varices to obliterate them. (Band ligation of the varices is analogous to rubber banding of hemorrhoids.)

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a non-surgical, radiologic procedure to decrease the pressure in the portal vein. TIPS is performed by a radiologist who inserts a stent (tube) through a neck vein, down the inferior vena cava, and into the hepatic vein within the liver. The stent then is placed so that one end is in the high-pressure portal vein and the other end is in the low-pressure hepatic vein. This tube shunts blood around the liver and by so doing lowers the pressure in the portal vein and varices and prevents bleeding from the varices. TIPS is particularly useful in patients who fail to respond to beta-blockers or variceal banding. TIPS also is useful in treating patients with ascites that do not respond to salt and fluid restriction and diuretics. TIPS can be used in patients with cirrhosis to prevent variceal bleeding while the patients are waiting for liver transplantation. The most common side effect of TIPS is hepatic encephalopathy. Another major problem with TIPS is the development of narrowing and blocking (occlusion) of the stent, causing recurrence of portal hypertension and variceal bleeding and ascites. Fortunately, there are methods to open blocked stents. Other complications of TIPS include bleeding due to inadvertent puncture of the liver capsule or a bile duct, infection, heart failure, and liver failure.

- A surgical operation to create a shunt (passage) from the high-pressure portal vein to veins with lower pressure can lower blood flow and pressure in the portal vein and prevent varices from bleeding. One procedure is called distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS). A surgical shunt may be considered for patients with portal hypertension who have early cirrhosis. The risks of major shunt surgery in these patients are less than in patients with advanced cirrhosis. During DSRS, the surgeon detaches the splenic vein from the portal vein and attaches it to the renal vein. Blood is then shunted from the spleen around the liver, lowering the pressure in the portal vein and varices and preventing bleeding from the varices.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.

Treatment for hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy

Patients with an abnormal sleep cycle, impaired thinking, odd behavior, or other signs of hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Dietary protein is restricted because it is a source of toxic compounds that cause hepatic encephalopathy. Lactulose, which is a liquid, traps toxic compounds in the colon so they cannot be absorbed into the bloodstream, and thus cause encephalopathy. Lactulose is converted to lactic acid in the colon, and the acidic environment that results is believed to trap the toxic compounds produced by the bacteria. To be sure adequate lactulose is present in the colon at all times, the patient should adjust the dose to produce 2 to 3 semiformed bowel movements a day. Lactulose is a laxative, and the effectiveness of treatment can be judged by loosening or increasing the frequency of stools. Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is an antibiotic taken orally that is not absorbed into the body but rather remains in the intestines. It is the preferred mode of treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Antibiotics work by suppressing the bacteria that produce the toxic compounds in the colon.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Treatment for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis complications

Patients suspected of having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis usually will undergo paracentesis. The fluid that is removed is examined for white blood cells and cultured for bacteria. Culturing involves inoculating a sample of the ascites into a bottle of nutrient-rich fluid that encourages the growth of bacteria, thus facilitating the identification of even small numbers of bacteria. Blood and urine samples also are often obtained for culturing because many patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis also will have infections in their blood and urine. Many doctors believe the infection may have begun in the blood and the urine and spread to the ascitic fluid to cause spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics such as cefotaxime (Claforan). Patients usually treated with antibiotics include:

- Ascites fluid cultures that contain bacteria.

- Patients without bacteria in their blood, urine, and ascitic fluid but who have elevated numbers of white blood cells (neutrophils) in the ascitic fluid (greater than 250 neutrophils/cc). Elevated neutrophil numbers in ascitic fluid often mean there is a bacterial infection. Doctors believe the lack of bacteria with culturing in some patients with increased neutrophils is due either to a very small number of bacteria or ineffective culturing techniques.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious infection. It often occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis whose immune systems are weak, but with modern antibiotics and early detection and treatment, the prognosis of recovering from an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is good.

In some patients, oral antibiotics (norfloxacin [Noroxin] or sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim [Bactrim]) can be prescribed to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Not all patients with cirrhosis and ascites should be treated with antibiotics to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but some patients are at high risk for developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and warrant preventive treatment.

- Patients with cirrhosis who are hospitalized for bleeding varices have a high risk of developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and should be started on antibiotics early during the hospitalization to treat presumed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- Patients with recurring episodes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- Patients with low protein levels in the ascitic fluid (ascitic fluid with low levels of protein is more likely to become infected).

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

Prevention and early detection for liver cancer, and liver transplantation

Prevention and early detection of liver cancer

Several types of liver disease that cause cirrhosis (such as hepatitis B and C) are associated with a high incidence of liver cancer. It is useful to screen for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, as early surgical treatment or transplantation of the liver can cure the patient of cancer. The difficulty is that the methods available for screening are only partially effective, identifying at best only half of patients at a curable stage of their cancer. Despite the partial effectiveness of screening, most patients with cirrhosis, particularly hepatitis B and C, are screened yearly or every six months with ultrasound examination of the liver and measurements of cancer-produced proteins in the blood, for example, alpha-fetoprotein.

Liver transplantation

Cirrhosis is irreversible. Liver function usually gradually worsens despite treatment, and complications of cirrhosis increase and become difficult to treat. When cirrhosis is far advanced liver transplantation often is the only option for treatment. Recent advances in surgical transplantation and medications to prevent infection and rejection of the transplanted liver have greatly improved survival after transplantation. On average, more than 80% of patients who receive transplants are alive after five years. Not everyone with cirrhosis is a candidate for transplantation. Furthermore, there is a shortage of livers to transplant, and they're usually is a long (months to years) wait before a liver for transplanting becomes available. Measures to slow the progression of liver disease, and treat and prevent complications of cirrhosis are vitally important.

What is the prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver?

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

- In compensated cirrhosis, patients have not developed any major complications and the average survival rate is more than 12 years.

- The prognosis for is worse for patients who have decompensated cirrhosis and have developed complications such as ascites, variceal hemorrhage, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatorenal syndrome, or hepatopulmonary syndrome. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis often require liver transplantation and in those who are unable to receive an organ transplant, life expectancy may be less than 6 months.

What research is ongoing to prevent and treat cirrohsis of the liver?

Progress in the management and prevention of cirrhosis continues. Research is ongoing to determine the mechanism of scar formation in the liver and how this process of scarring can be interrupted or even reversed. Newer and better treatments for viral liver disease are being developed to prevent the progression to cirrhosis. Prevention of viral hepatitis by vaccination, which is available for hepatitis B, is being developed for hepatitis C. Treatments for the complications of cirrhosis are being developed or revised, and tested continually. Finally, research is being directed at identifying new proteins in the blood that can detect liver cancer early or predict which patients will develop liver cancer.

A cirrose é uma complicação da doença hepática que envolve perda de células hepáticas e cicatrização irreversível do fígado.

A cirrose é uma complicação da doença hepática que envolve perda de células hepáticas e cicatrização irreversível do fígado.  Existem muitas causas de cirrose, incluindo produtos químicos (como álcool, gordura e certos medicamentos), vírus, metais e doença hepática autoimune em que o sistema imunológico do corpo ataca o fígado.

Existem muitas causas de cirrose, incluindo produtos químicos (como álcool, gordura e certos medicamentos), vírus, metais e doença hepática autoimune em que o sistema imunológico do corpo ataca o fígado.  A relação do fígado com o sangue é única.

A relação do fígado com o sangue é única.  Os sintomas e sinais comuns de cirrose incluem icterícia, fadiga, fraqueza, perda de apetite, coceira e hematomas fáceis.

Os sintomas e sinais comuns de cirrose incluem icterícia, fadiga, fraqueza, perda de apetite, coceira e hematomas fáceis.  Edema, ascite e complicações de peritonite bacteriana

Edema, ascite e complicações de peritonite bacteriana  Sangramento e complicações do baço

Sangramento e complicações do baço  Complicações hepáticas (hepáticas)

Complicações hepáticas (hepáticas)  Existem 12 causas comuns de cirrose.

Existem 12 causas comuns de cirrose.  Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.  Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.  Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.  Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.  There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.  Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.  Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.  Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.  Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.  The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.  Sintomas de má absorção de ácidos biliares, diagnóstico e guia de tratamento

Sintomas de má absorção de ácidos biliares, diagnóstico e guia de tratamento

O vírus Ebola é contagioso?

O vírus Ebola é contagioso?

Precisamos de sua ajuda com os suplementos legais SCD

Precisamos de sua ajuda com os suplementos legais SCD

Defecação dissinérgica:sobre uma causa comum de constipação crônica

Defecação dissinérgica:sobre uma causa comum de constipação crônica

Neil Bell nomeado Diretor de Desenvolvimento da Avacta Life Sciences

Neil Bell nomeado Diretor de Desenvolvimento da Avacta Life Sciences

Como você cura hemorróidas?

Como você cura hemorróidas?

Ray Manzarek morre de câncer de ducto biliar

Venice Beach, Califórnia, 1965. Por sorte, Ray Manzarek encontra Jim Morrison, um ex-colega de classe da UCLA, e o mundo é abençoado com a música do The Doors. A banda vende 100 milhões de álbuns. R

Ray Manzarek morre de câncer de ducto biliar

Venice Beach, Califórnia, 1965. Por sorte, Ray Manzarek encontra Jim Morrison, um ex-colega de classe da UCLA, e o mundo é abençoado com a música do The Doors. A banda vende 100 milhões de álbuns. R

O estresse pode prejudicar seu estômago

Você provavelmente já ouviu falar que o estresse pode causar estragos em praticamente todas as partes do seu corpo e mente. O estresse crônico pode exacerbar muitos problemas de saúde graves: Saúde m

O estresse pode prejudicar seu estômago

Você provavelmente já ouviu falar que o estresse pode causar estragos em praticamente todas as partes do seu corpo e mente. O estresse crônico pode exacerbar muitos problemas de saúde graves: Saúde m

O estudo sugere uma ligação entre o uso de probióticos e "nebulosidade do cérebro"

Um estudo realizado no Medical College of Georgia na Augusta University mostrou que a ingestão de probióticos pode resultar em um acúmulo significativo de bactérias do intestino delgado que leva ao em

O estudo sugere uma ligação entre o uso de probióticos e "nebulosidade do cérebro"

Um estudo realizado no Medical College of Georgia na Augusta University mostrou que a ingestão de probióticos pode resultar em um acúmulo significativo de bactérias do intestino delgado que leva ao em